By Kevli Sheth

Blue-Skinned Women in Benjamin’s Finding Home and Exodus Series

Gouache, acrylic and gold leaf on wood panel

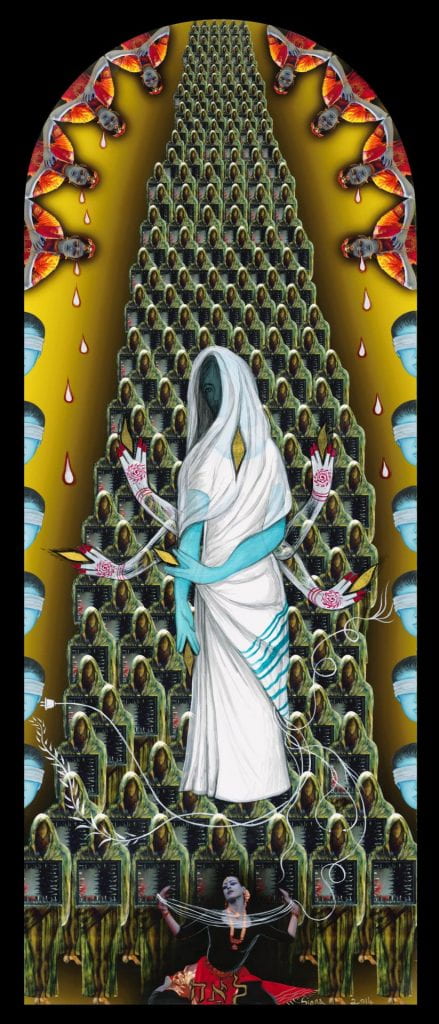

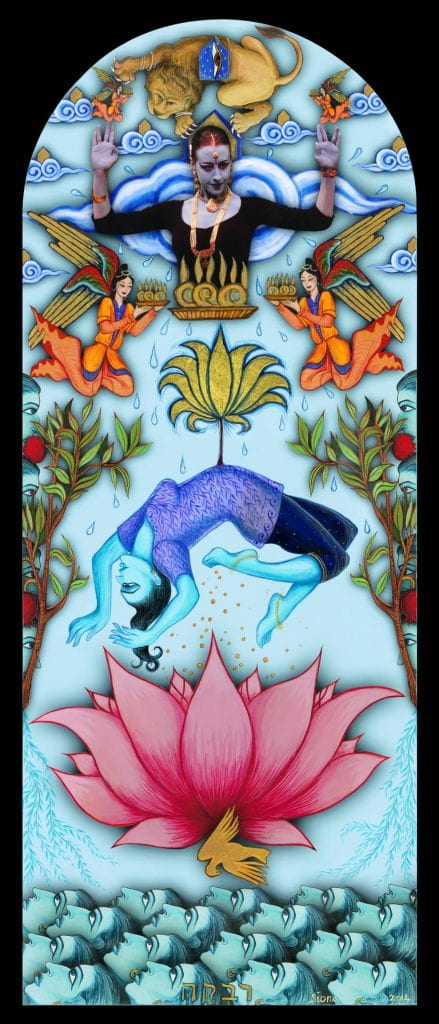

The Four Mothers Who Entered Pardes (Rachel, Sara, Leah, Rebecca)

Total installation size: 6 feet tall x 12 feet wide

Hand embellished and archival prints on canvas

GALLERY TALK: The Four Mothers Who Entered Pardes

Transcript

The rabbinic tale of The Four Who Entered Pardes centers on four rabbis: Rabbis ben Azzai, ben Zoma, Elisha, and Akiva. These men enter Pardes, most commonly translated as paradise, and Rabbi ben Azzai dies, Rabbi ben Zoma goes mad, Rabbi Elisha loses his faith, but Rabbi Akiva returns, whole (Subtelny 5). The Four Who Entered Pardes has been read as both a “testimony of a mystical experience” and as a parable (Gottstein 88, 89). Siona Benjamin’s installation entitled The Four Mothers Who Entered Pardes seems to understand the original story as a parable without a definite moral. She reimagines this ancient story by centering four biblical matriarchs who are, from left to right, Rachel, Sara, Leah, and Rebecca. Through these women, Benjamin visually elaborates on exile, womanhood, and modernity. Her installation functions as a visual midrash,or creative retelling, of this rabbinic lore, but it diverges from many other renditions of this story in rabbinic, medieval, and mystical Jewish literature. Many interpretations of this tale focus upon what the rabbis themselves may or may not have done to affect their fates. In many ways, Benjamin’s work, The Four Mothers Who Entered Pardes, also explores why these different ancestral women experience Paradise as they do, but she also seems to suggest that both Paradise and the world are imperfect and it is the expectation of perfection that may, in fact, be what prevents contentment whether one is within or out of Paradise.

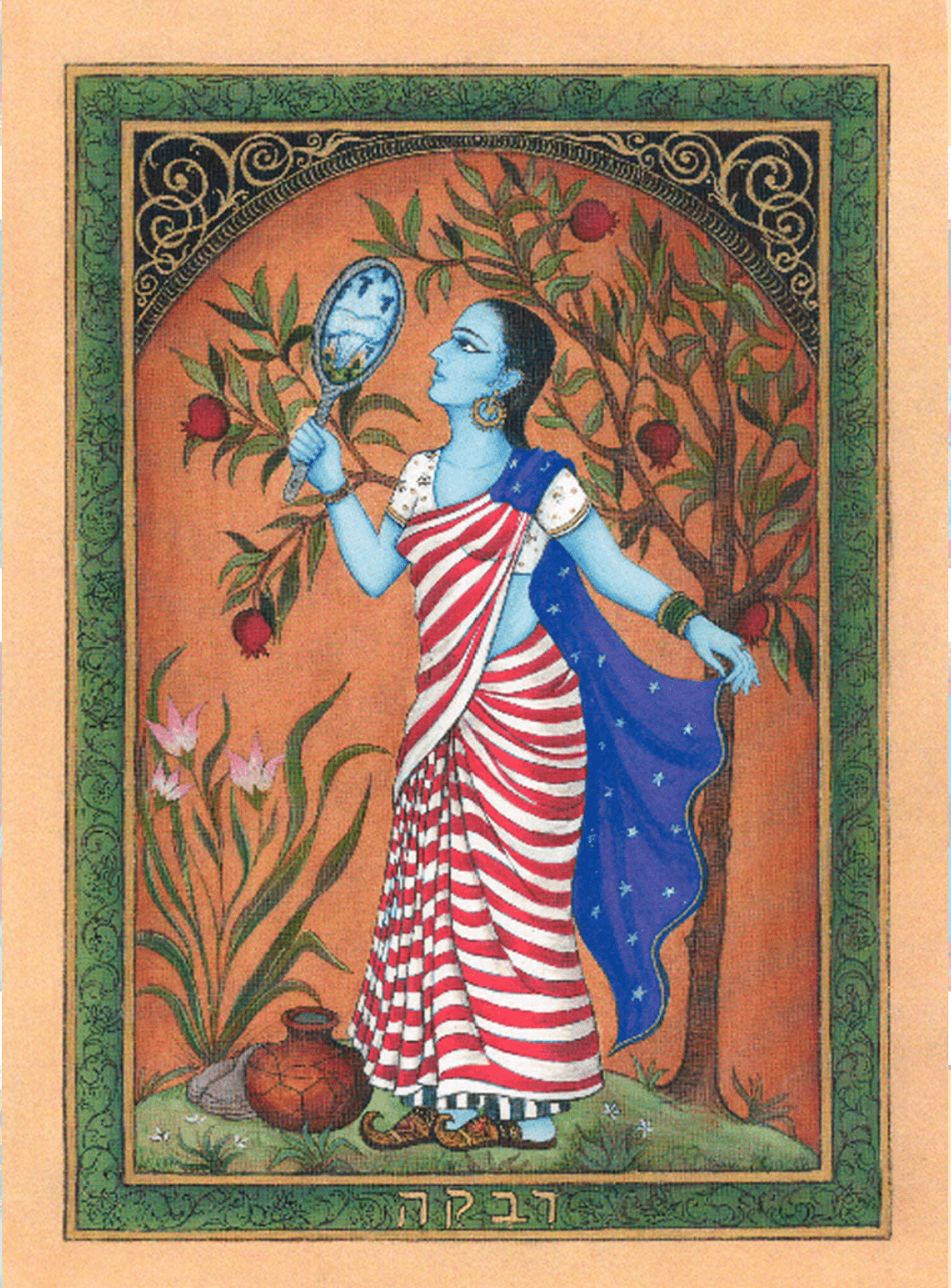

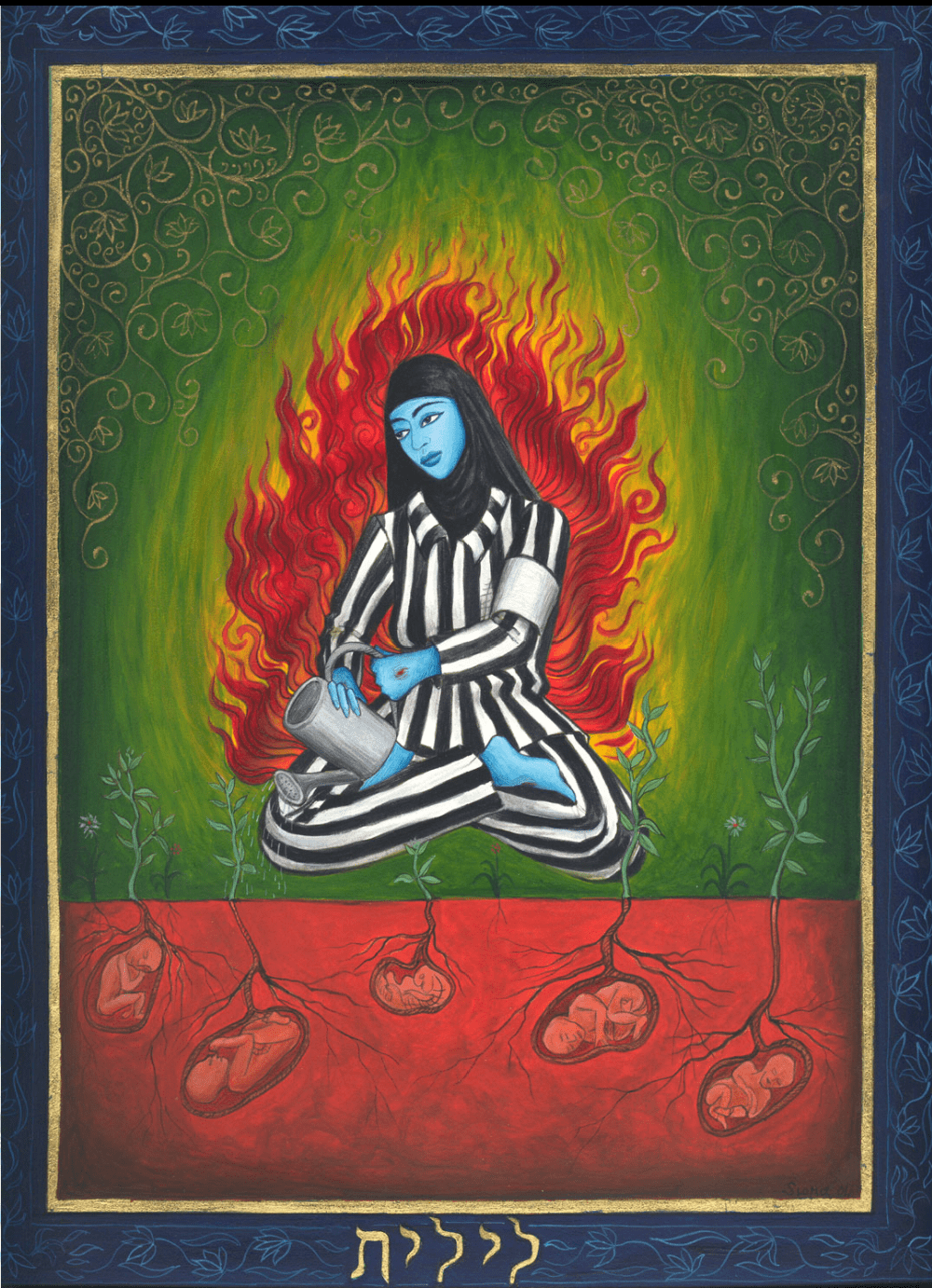

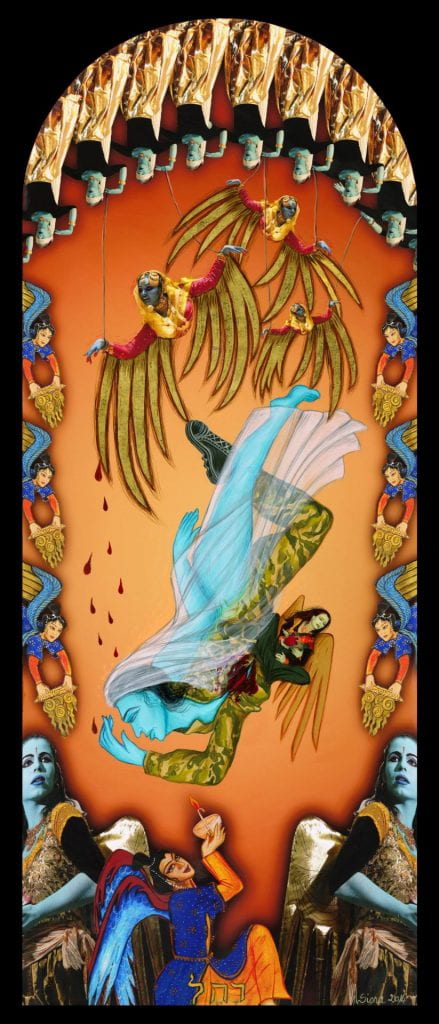

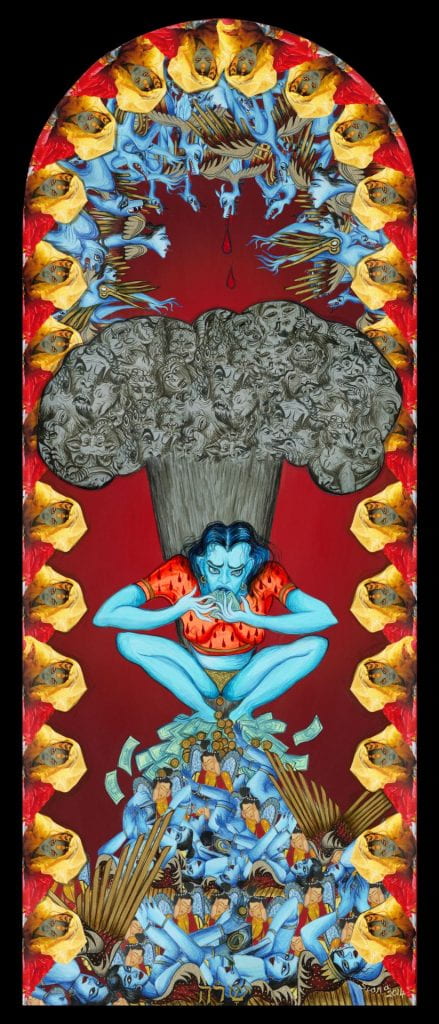

The term Pardes is often read to refer to Paradise, but, in Hebrew, the word also means orchard. The Persian Achaemenids also associated that word with royal palace gardens, which were heavily guarded (Subtelny 17-18). The idea of a limited-access Paradise is referenced in Benjamin’s piecebecause the women can enter Paradise, but only one matriarch, Rebecca, returns peacefully, just as Rabbi Akiva does in the original Pardes story. Both the original tale and Benjamin’s reconfiguration of it reference the Jewish experience of exile. Three of the four central characters cannot return to who they were before entering Paradise, and they are forever prevented from truly experiencing all of Paradise. They live in a liminal space, not fully in Paradise and yet not fully out of it. Thus, these three figures are exiled from two worlds. In his work, Galut: Modern Jewish Reflection on Homelessness and Homecoming, scholar Arnold Eisen writes, “Paradise, it seems, has never preoccupied the Jewish imagination nearly so much as exile” (xi). Benjamin’s artwork corroborates his statement. The theme of exile is also addressed in Benjamin’s Finding Home series and her installation entitled Exodus: I See Myself in You. In this work, migrants from many eras find themselves locked out of the Garden of Eden. It seems that her vision of a homeland is, as Eisen describes, “shaped…by inherited pictures of homelessness” (xiii). Jewish text is also seen as a garden because the further one wanders into it through interpretation, the more one can see and, thus, understand. There are many interpretative methods used to engage with Jewish texts, ranging from literal interpretations to the mystical. Benjamin applies such methods in her interpretation of the original Pardes story and the matriarch’s tales. One can also engage in those interpretative processes with Benjamin’s installation as well. The further one immerses themselves into her work, the more one can gain from the experience.

Siona Benjamin reflects upon themes of exile and Paradise by reimagining The Four Who Entered Pardes through the lens of the biblical stories of the matriarchs, Rachel, Sara, Leah, and Rebecca. In the installation, all the women are blue-skinned, a motif in Benjamin’s mythology that symbolizes what difference means for marginalized people by overtly distinguishing them from other elements in a piece. The color blue also indicates universality in Benjamin’s work because, as Benjamin says, it is “the color of the sky and the ocean.” In her work, blue-skinned figures blur borders that exist between the divine and the mortal and between national and religious identities. In Benjamin’s installation, the matriarchs’ blue skin draws attention to them, intentionally recentering them within a text that historically cast women as peripheral. She reaffirms that the matriarchs’ lives are essential to everyone’s survival and are a legitimate method of meditating on divinity. The women’s blue skin also indicates that they are physically “in-between,” in terms of location. The first three women are not fully in Paradise, but they are not of the mortal world either. Even Rebecca, the matriarch in the fourth panel, is not yet completely descended from Paradise; she is in transit. Their bodies, both in their blue skin and their physical positions, are not divine and not mortal, not of one place or another. Their liminality represents those who have been forcibly displaced as well as the universal experience of feeling othered. Because the matriarchs are not in Paradise or the mortal world, they can be used to reflect upon war, greed, uncertainty, and imperfection, struggles that exist in both worlds.

Siona Benjamin works within the tradition of American Jewish feminist modern midrashim and Black womanist biblical interpretation that began in the 1960s and 1970s (Hyman). To illuminate Benjamin’s interpretations of the four matriarchs, I place them into conversation with the original Pardes story and the midrashim of Black womanist biblical scholar Wilda Gafney, who draws upon the Jewish tradition of midrash in her book Womanist Midrash: A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and the Throne.

Rachel dies in childbirth in her biblical story. To Wilda Gafney, Rachel’s story resonates with the generational trauma embodied by enslaved African American women, women who were often separated from their mothers and their children were often taken from them (62). In Gafney’s interpretation of Rachel’s story, Rachel was motherless for much of her life, and then because she herself died in childbirth, her child is set to suffer the same fate. Benjamin’s depiction of Rachel showcases the generational trauma that war can induce, as suggested by Rachel bleeding in a soldier’s uniform, the angels unable to help her. Rachel represents the figure of a mother grieving her child, a figure that has existed throughout cultures and history and a figure that is reproduced by war into the present.

Wilda Gafney understands Sara’s story as an example of how one can “[exercise] privilege” while “experienc[ing] peril” (38). In Gafney’s interpretation, powerful men objectify Sara throughout her life, but, despite facing sexism herself, Sara’s infertility fuels her jealousy of Hagar, her Egyptian handmaid and surrogate. Sara abuses Hagar even after she conceives a child, including by exiling Hagar into the wilderness (Gafney 37). One can read the dynamic of privilege and marginalization in Benjamin’s retelling of Sara’s story as well. In Benjamin’s installation, the second panel references the biblical stories of the Binding of Isaac/Akedah and the Life of Sara/Chayei Sara (Gen. 22-23). In the Binding of Isaac, Abraham takes his son, Isaac, to the mountain to sacrifice him for God. Ultimately, God recants his request, and Isaac is not sacrificed. The Torah portion that follows is called the Life of Sara/Chayei Sara, and it begins with Sara’s death (Gen. 23). Many rabbinic interpreters have understood this ordering to mean that Sara dies after she hears that Abraham has taken her miracle child, Isaac, to die. Though Isaac does not die, the rabbinic interpreters presume that Sara never learns this. Benjamin’s retelling of Sara’s story works from this same presumption that Sara believes her child to have been killed without her or the child’s input as if they are property. Benjamin shows Sara going mad with greed, thereby paralleling the original Pardes story, in which Rabbi ben Zoma goes mad from seeing Paradise. However, Benjamin’s version of Sara’s madness imagines her participating in the greed of the world, both by objectifying and violating Hagar and by literally eating money. The panel speaks to the greediness of global economic, political, and social systems, which extracts from the exploited like Sara and Hagar. However, because these greedy systems are foundational to the modern world, they force even the exploited to participate and compete with one another to gain status in a hierarchy that does not serve them, thus reifying that same hierarchy. The fact that divine commands and figures drove Sara to madness suggests that Paradise is imperfect, just as the modern world is.

Benjamin continues to question the perfection of Paradise in her third panel in which she retells Leah’s story. In the biblical narrative Leah is weak of sight and is not the true beloved of Jacob; in this way, devalued, she suffers. Yet, unlike Rachel who gives birth to only one child herself, having her others through surrogates, Leah has many children. In Gafney’s retelling, Leah’s children suffer, and she is only deemed a matriarch after she is dead (Gafney 66). Gafney sees her as a “cautionary tale [of how] you cannot make someone love you” (67). Leah’s counterpart in the original Pardes story is Rabbi Elisha, who becomes a heretic. However, despite the fact that she cannot pass through Paradise, Leah is not imagined as a heretic in Benjamin’s retelling. Benjamin gives Leah a resolution; she is surrounded by blindfolded women, seemingly in an act of solidarity, for Leah’s blindness is not a negative symbol. In fact, she may be more aware of other aspects of the world, like the importance of solidarity over perfection, because of it. One may read this depiction of Leah as an acknowledgment that there is much we cannot see, including within Paradise. Despite her suffering, Leah has found an inner strength and community that she nor Rabbi Elisha had in their stories. She is comfortable with the uncertainty in the world, disrupting the idea that one must find the place of ultimate peace to be content.

In the final panel of the installation, we see Rebecca’s ascent into Paradise. Her equivalent in the original Pardes story is Rabbi Akiva, who, in a Persian analysis by Maria Subtelny, could pass through Paradise because he understands the complexity of God’s existence (40). Similarly, Rebecca is the only matriarch to whom God speaks directly, relating a prophecy to her about the children in her womb. Because of her agency in her biblical stories, Rebecca has been read as conniving. Nonetheless, she still can move through Paradise. By displaying a flawed woman as Rabbi Akiva’s equivalent, Benjamin implies that Paradise is flawed and complex, just like the world outside of it. Because Rebecca understands this through her connection to the divine, she can be content within Paradise and therefore pass through it. This final panel truly blurs the line between the divine and the mortal, demonstrated by its intense blue hues, because it shows that both worlds are imperfect and the acceptance of this leads to peace.

Women are empowered in Siona Benjamin’s work because she recognizes the matriarchs as legitimate ancestors of Jewish people and as an access point to the divine. She compounds her statement on the strength of womanhood by painting the women in a different order than they are usually referenced. When progressive movements of Judaism reference the matriarchs, the women are typically listed in chronological order—Sara, Rebecca, Leah, and Rachel. However, Benjamin paints them in the order Rachel, Sara, Leah, then Rebecca. By taking them out of chronological order, the audience can recognize each woman as a matriarch in her own right, her story powerful no matter when it is told. Additionally, Benjamin’s insights on war, greed, and imperfection are made more impactful in that she communicates through matriarchs. For example, the audience sees the effect of war on Rachel and, because she is a mother, they can understand that her harm translates to the harm of her children. Benjamin utilizes the audience’s association between women and family to reflect on how modern conflicts break families, and, because this disrupts the flow of tradition, the conflicts break nations (Mani 90, Mankeker 250-252). Because the blue matriarchs embody liminality, they encourage the audience to think about how their identities have been constructed and can therefore be complicated. The matriarchs’ suffering uplifts how people suffer when they reinforce their identities through war, greed, and the constant pursuit of perfection. Showcasing women as the access point of divinity and using them to inspire self-reflection can be empowering, but Benjamin ensures that we see the matriarchs as human by showing their flaws and their contentment alongside their suffering. Women’s deaths often are used to galvanize people to protect their families and nations because they symbolize the disruption of the family and tradition (Mankekar 251). However, it is not the job of women to be martyred. Benjamin depicts flawed women who still find contentment, like Leah and Rebecca, and, although Rachel and Sara suffer, it is not glorified. The humanization of the matriarchs confronts the audience with their responsibility to deconstruct the walls of Paradise and to realize contentment outside of Paradise by acknowledging universal imperfections.

Sources

Eisen, Arnold M. “Introduction.” Introduction. In Galut: Modern Jewish Reflection on Homelessness and Homecoming, xi–xx. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1986.

Gafney, Wilda. Womanist Midrash: A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and the Throne. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2017.

Gottstein, Alon Goshen. “Four Entered Paradise Revisited.” Harvard Theological Review 88, no. 1 (1995): 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1017/s001781600003039x.

Hyman, Paula E. “Jewish Feminism in the United States.” Jewish Women’s Archive, 2021. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/jewish-feminism-in-united-states.

Mani, Lata. “Recasting Women.” Chapter. In Contentious Traditions: The Debate on Sati in Colonial India, 88–126. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007.

Mankekar, Purnima. “Chapter 5: Television Tales, National Narratives, and a Woman’s Rage: Multiple Interpretations of Draupadi’s ‘Disrobing.’” Essay. In Screening Culture, Viewing Politics: An Ethnography of Television, Womanhood, and Nation Postcolonial India, 225–56. Brantford, Ontario: W. Ross MacDonald School Resource Services Library, 2009.Subtelny, Maria E. “The Tale of the Four Sages Who Entered the Pardes: A Talmudic Enigma from a Persian Perspective.” Jewish Studies Quarterly 11, no. 1-2 (2004): 3–41. https://doi.org/10.1628/0944570043028527.

Subtelny, Maria E. “The Tale of the Four Sages Who Entered the Pardes: A Talmudic Enigma from a Persian Perspective.” Jewish Studies Quarterly 11, no. 1-2 (2004): 3–41. https://doi.org/10.1628/0944570043028527.