Sarah Hancock

Gallery Talk

Transcript

Throughout human history, art has existed as a method to depict ideas, whether that be the task of showing the world around you as you see it or the more daunting task of using shared themes and concepts to create a legible narrative. One such task that has plagued and puzzled artists for centuries is the depiction of paradise. How can we show something so foreign to us in a two-dimensional space? How do we imagine the unimaginable?

Paradise is a concept often referenced in discussions revolving around diaspora, and within the Jewish diaspora, the concept of paradise is especially prevalent. The idea of paradise–Zion–informs many Jewish practices and rites; it has strong roots in much of the everyday liturgy. Isaiah 33.20 says of Zion, “When you gaze upon Zion, our city of assembly, Your eyes shall behold Jerusalem As a secure homestead, A tent not to be transported, Whose pegs shall never be pulled up, And none of whose ropes shall break” (Fishbane et al).

Siona Benjamin’s Exodus: I See Myself in You provides a sort of call to action that plays into these ideas of Paradise. She blends the realistic–refugees and downtrodden people making their way through the world–with the sublime–swirling figures of blue against frames of shimmering gold. In this way, she is simultaneously creating a space that is of this world and not. It is present but also unreachable, a common theme in descriptions of paradise in Jewish practices. We must wonder if this is the whole point. Does it matter that Zion can be reached–a tangible center, or does it simply need to be? These are questions that became especially prevalent in the literature of early Zionist thinkers, such as Theodor Herzl, who suggested that if the creation of a Jewish state could “…be described by a single word, let it be labeled not as ‘fantasy,’ but at most a ‘construction’” (Herzl). This places importance on the act of creation itself; rather than waiting for this place, they need to make it themselves. These themes carry over into Benjamin’s piece. As Dr. Aaron Rosen so eloquently puts it, “Maybe we have left Paradise, maybe we have lost it forever. But perhaps, this story teaches us, it can still save us. This is Siona Benjamin’s offering.”

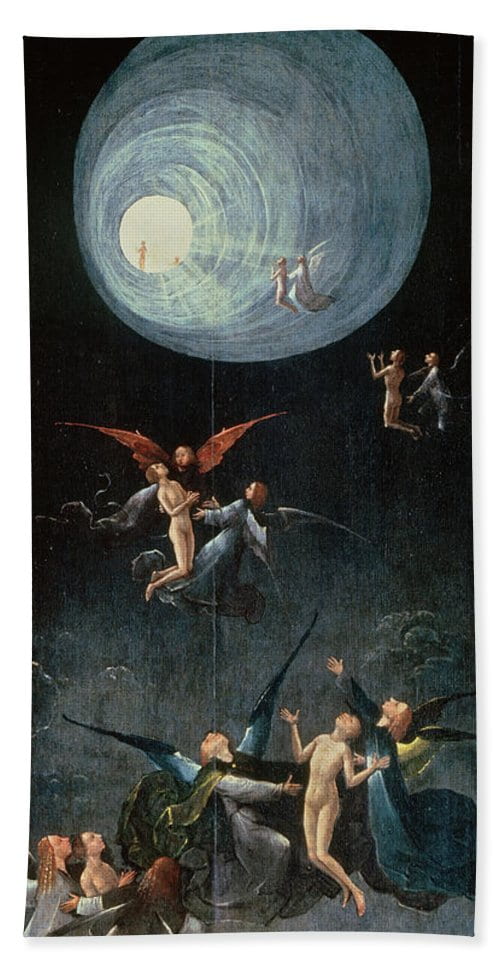

In stark contrast, Hieronymus Bosch’s Ascent of the Blessed, one panel of a triptych, shows heaven as a disc of light floating high in the sky. It’s almost like he has created this fictional tunnel for each viewer to pass through in order to reach this predetermined destination. His figures lack defining characteristics, making it easier for his audience to apply themselves to each form. Although Christian theology has some of the most descriptive renderings of heaven, Bosch’s paradise is a place so outside the realm of human understanding that it has been rendered down to its barest essentials–nothing but a form on paper. Within this faith, paradise is a constant. It has been laid out since the dawn of time, and ultimately its form will never be affected by our actions on Earth.

I believe that this parallel shows a deeper reflection on the effects of expulsion–the effects of living in diaspora–on a community’s understanding of paradise. Jewish people were driven out of their home, and treasure and honor it in different ways because of that. This expulsion has shaped Jewish tradition and changed it forever from what it was at its beginning. American Judaic scholar Arnold Eisen states, “Deprived of the sacred center, the rabbis pointed to it all the more insistently, even as they enabled Jews to live their lives–with God–outside it” (Eisen). Benjamin’s piece has many components that lend themselves to this specific understanding of paradise, tied all the more closely together with traditional imagery of rams, whales, and other religious stories. They speak to not only the hardships of being a refugee but also the dreams that sustain that journey.

The years that span between these two pieces may suggest that there is, in fact, no connection to be made. That being said, by understanding how definitions of paradise change from communities that have remained in place and those that have been moved, we can better understand the themes of paradise in Siona Benjamin’s work. In this case, I believe that is the use of tangible, human stories to create a paradise on Earth–a home.

Sources

Fishbane, Michael A., Adele Berlin, and Marc Zvi Brettler. The Jewish Study Bible: Jewish Publication Society Tanakh Translation. New York: Oxford University Press: 2004

Eisen, Arnold. Galut: Modern Jewish Reflections on Homelessnes and Homecoming. Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1986.