—Tanner Ray

Gallery Talk on National Symbols and Civil Religion in Benjamin’s Work

Transcript

National Symbols and Civil Religion in Benjamin’s Work

Underneath the softened blues and whites of a tallit (prayer shawl), sunglasses–reflecting stars and stripes in the distance–cover the eyes of a still, cyan-colored figure. Rather than facing the direction of Jerusalem, as is common in Jewish prayer, the closed-eyes of the figure seemingly pierce through the gallery, keenly observing the profound colors of an American flag. In the center of the painting, the white stars shine proudly within a pool of handsome navy blue, and the red and white bars compose a patriotic vibrancy that strikes the heart of American observers. As one slowly approaches Benjamin’s American flag, the outer edges of the painting become prominent. The flag’s colors grow dull with each step, and a dark yellow slowly encompasses the vibrant red, white, and blue.

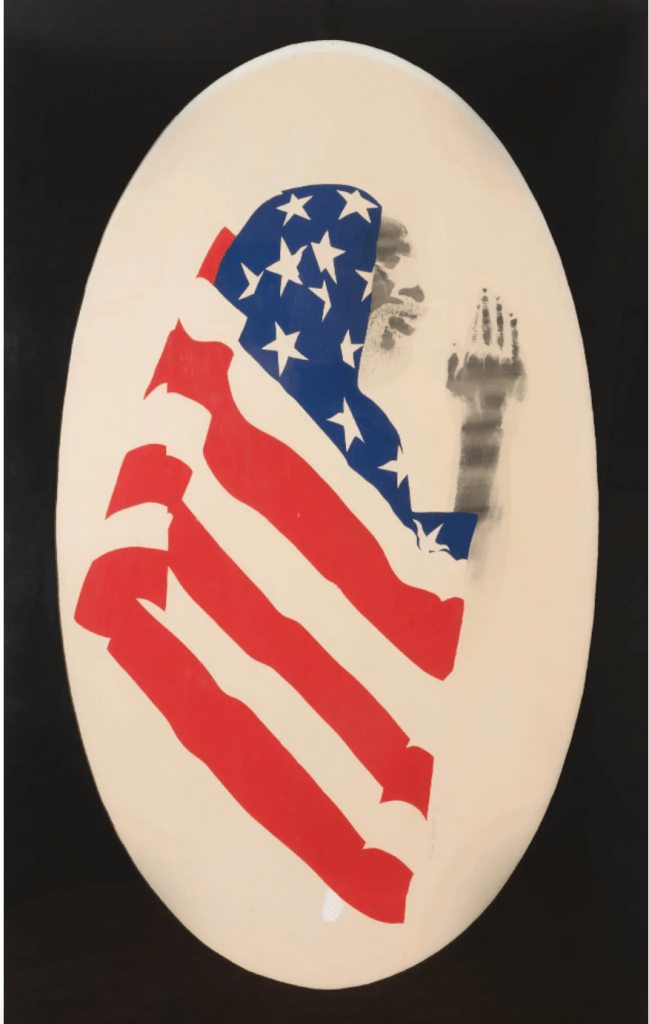

One will notice that Benjamin’s piece is not the smooth, perfectly proportionate flag that one would turn towards whilst placing their hand over their heart; instead, the painting consists of thick, lumpy brushstrokes that disperse color unevenly. Benjamin re-interprets the American flag, portraying it as stiff and unloving, yet violent and exclusive. Inside the red and white lines, Benjamin fills her painting with many sacred cultural and religious icons such as handguns, WWII era American propaganda images of Bugs Bunny holding a warhead, the Statue of Liberty, and her resident alien card. Benjamin’s artistic decision to use the flag as a canvas for exploring the relationship between culture, nationalism, and religion reflects the generally accepted sacrality of flags. Whether it waves smartly over an elementary school, burns on the ground, or lies in a triangular fold–star side showing–in the casket of a dead veteran, flags affirm the direct connection between patriotism and religion. Reacting to this phenomenon, scholars apply definitions of religion to other sacred symbols, thus displaying the existence of civil religion. For example, American anthropologist Clifford Geertz defines religion as: “A system of symbols which establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations by formulating conceptions of a general order and clothing these conceptions with such an aura that the motivations seem realistic” (Geertz, 5). Using Geertz’s definition, we see how singing the national anthem before a baseball game becomes a religious act and the Declaration of Independence a sacred text. These symbols and rituals bind particular group members through historical narratives, myths, and rituals (Kao and Copulsky, 125). Simultaneously, flags and other nationalist symbols establish distinct boundaries between nations, creating in-groups and out-groups for who has claims to a country. In Benjamin’s work with flags, she builds upon and critiques the normative symbolism associated with nationally-sacred objects. Going beyond re-thinking the flag and its function, Benjamin adds an entirely new dimension between nationality and identity: portraying a blue face underneath a Jewish prayer shawl facing the American flag, looking at the immense violence, and seeming to say to the loaded handguns, “Is this what you expect me to worship?”

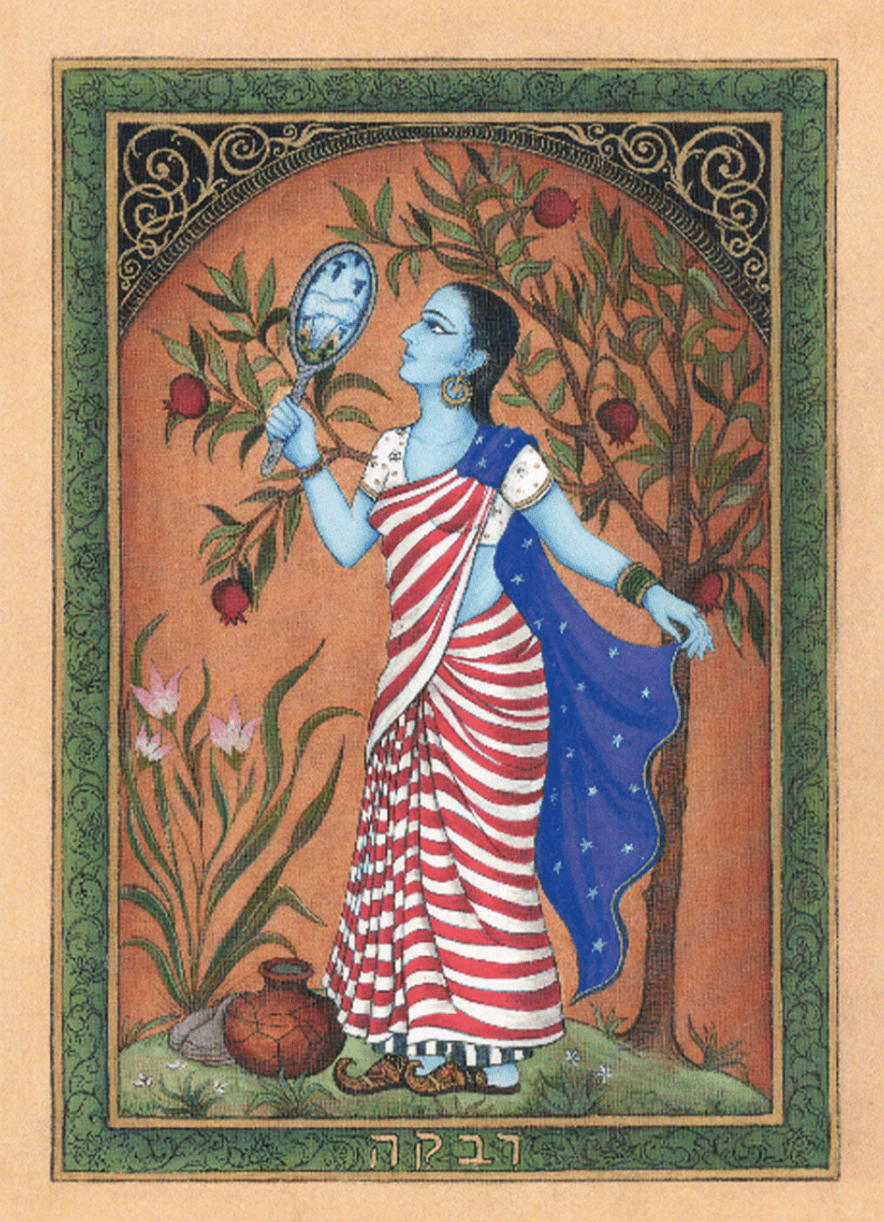

Benjamin explores how symbols, rituals, and traditions act as civil religion that constitutes a national identity- exploring how this national identity corresponds, or conflicts, with her unique mythology. In My America, Benjamin depicts the Statue of Liberty, a sculpture used to greet millions of immigrants on Ellis Island, with an ominous radiation hazard symbol over the body. At Benjamin’s hand, the torch Lady Liberty raises skywards, widely accepted to represent the light of freedom, comes to symbolize the flames of oppression faced by immigrants. Likewise, Benjamin includes a self-portrait near the top of the flag beside the words: Resident Alien. Already having received a green card at the time of completion, Benjamin’s choice to include her resident alien card suggests the consequences of a tiring, loathsome citizenship process which leaves one feeling not truly assimilated, trusted, or welcomed. The word ‘alien,’ in itself, sentences Benjamin to the status of ‘other.’ Without a sense of belonging, Benjamin’s decision to include these symbols provides commentary on her relationship towards America’s promise of refuge, nativism, and violence. While the flag welcomes Benjamin from far away, it perceives her as a threat up close. The blue figure remains distant, maintaining its unique identity through an unwillingness to shed her blue skin and abandon the tallit. Rather than renouncing the parts of her identity that America perceives as different or threatening, Benjamin chooses to celebrate them. Although America appears a particular way to citizens at birth, Benjamin uses symbolism to expose American society’s harsh, oppressive underbelly. Each symbol serves as shorthand for expressing Benjamin’s immensely complex relationship with nationalist identity and her lived experience of simultaneously belonging everywhere and nowhere. Benjamin’s symbols are not singular signs of patriotism; instead, they are post-modern critiques and reimaginations of patriotism’s critical function. Ultimately, Benjamin’s use of symbols demonstrates images’ role in the social construction of reality. Drawing upon the connection between nationalism and religion, Benjamin highlights how this association affects societal ideas of belonging, power, acceptance, liberation, and oppression.

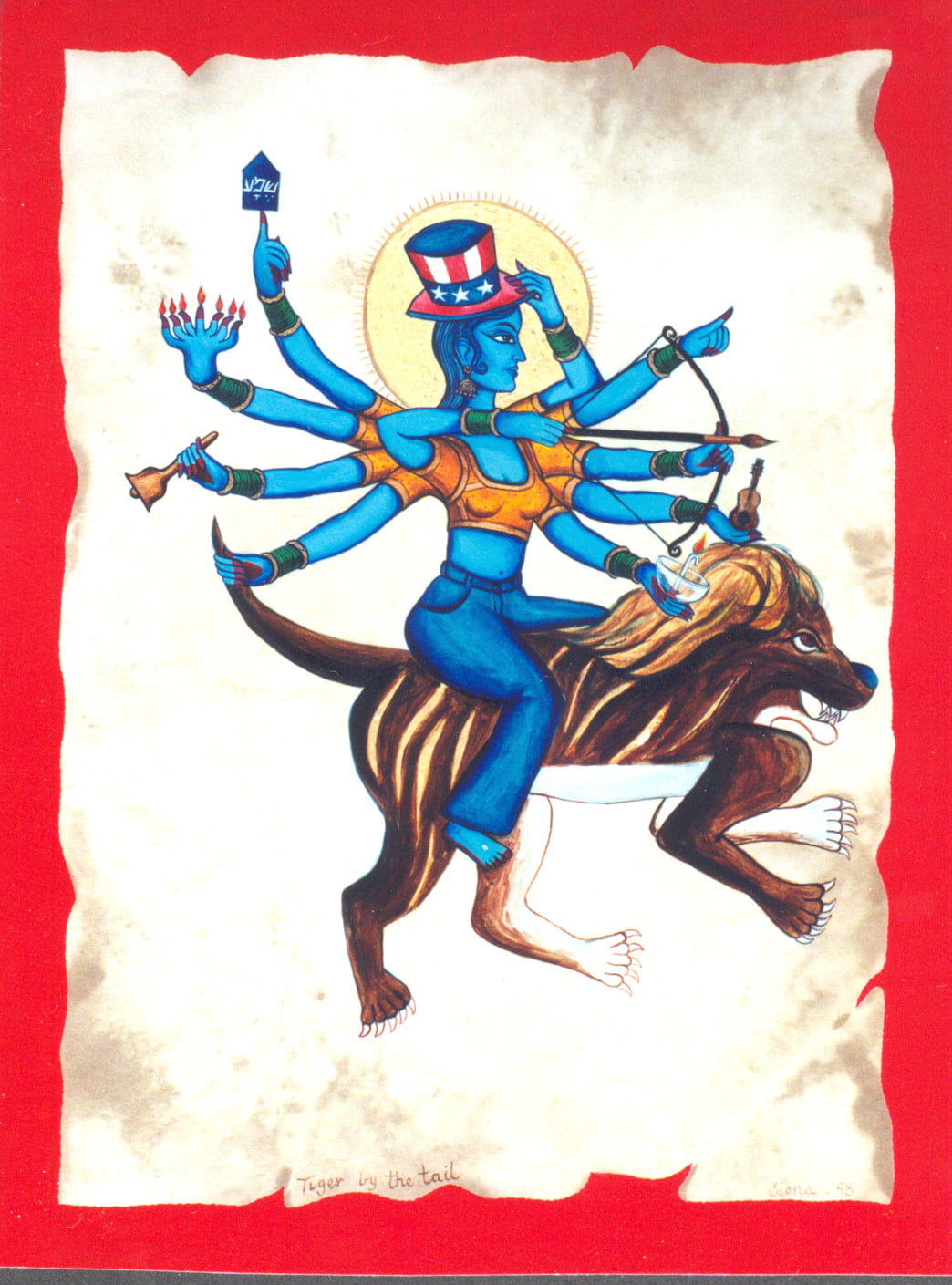

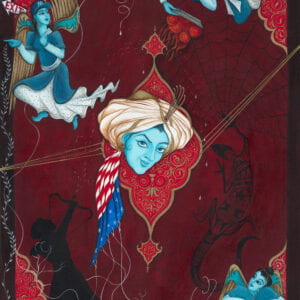

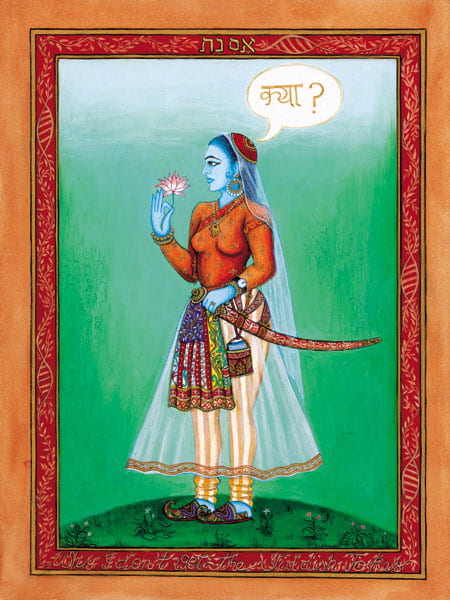

Benjamin’s use of flags and other national symbols, corresponding with her work as a whole, changes from piece to piece- open to many interpretations and analyses. Although My America exposes and critiques threatening aspects of American immigrant life, other works such as Finding Home #33 and Finding Home #87 (Lilith) use symbolism that displays an embrace of American identity. For example, Finding Home #33 portrays a six-armed Benjamin holding various sacred objects such as a menorah, a paintbrush, and the Shema, which cries, “Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is one.” Above each symbol, held in careful fingers and tipped slightly downwards, is an Uncle Sam cap that proudly displays the Star of David underneath red and white stripes. Combining national and sacred symbols from many cultural backgrounds represents Benjamin’s nuanced identity. The blue skin, exemplifying the azure hues of the sky and sea, celebrates belonging everywhere and nowhere. An observer can compare the objects in Benjamin’s hands to jigsaw pieces, each item completing an intricate puzzle of self-expression. Likewise, Finding Home #87 displays Lilith, Adam’s intended first wife and a symbol of post-modern feminism, wearing an American flag with Persian-style angel wings protruding from the end. Blue figures wearing Yankees caps surround her, appearing clever and confident. Again, the wings protruding from the angels and flags demonstrate the connection between nationality, religion, and selfhood. One can compare this work with Shepard Fairey’s artistic prints depicting hijabi women wearing the American flag as a headscarf. Through a comparative analysis of the two works, we understand how immigrant communities demonstrate patriotism to create a better assimilation process. Likewise, these works force the observer to ask themselves, “What does it mean to see someone deemed as the ‘other’ draped in the American flag?” Together, these symbols work to reveal the other side of the civil-religion coin, the side Benjamin and additional immigrants use to become accepted within a larger nativist society.

The visual dialogue that Benjamin’s piece establishes between the cyan-colored figure and the familiar motif of an American flag displays how the act of seeing is an operation that relies upon an apparatus of previously learned assumptions and inclinations, habits, routines, historical situations, and cultural practices (Morgan, 3). We might interpret how the blue figure, engaged in prayer for herself, other immigrants, or a more equitable America, sees the flag, and is seen by it, as mimicking the Hindu act of darshan- an encounter of divine seeing that is reciprocal, a devotee sees an image of the Divine with the Divine returning the gaze. (Morgan, 48). Benjamin observes the flag as a nationalist object; the flag sees her back. The dialogue between the blue figure and the flag is an intimate metaphor that demonstrates how the concept of the gaze impacts those deemed as perpetually ‘other.’ The prayer shawl and blue skin highlight a difference between Benjamin and nativist society. As seen in the flag, the violence demonstrates the oppressive consequences that those deemed as ‘alien’ face. However, as the flag sees Benjamin back, it recognizes her newfound identity as an American.

Although Benjamin does not mean to suggest that the figure is worshipping the flag, as one might do in the act of darshan, the reverence and reciprocity that the practice of darshan involves proves a helpful lens through which we perceive how the gaze functions. According to scholar David Morgan, the “sacred gaze” involves a distinct composition of ideas, attitudes, and customs that exhibit the spiritual act of seeing within a cultural and historical setting (Morgan, 3). The gaze requires an observer, the subject of view, the content of the issue, and the regulations governing the relationship between observer and subject (Morgan, 3). A thorough understanding of the gaze and its operations introduces the viewer to a more nuanced knowledge of the social function of images and their relation to gender, status, religion, nationality, and race (Morgan, 22).

Benjamin, heavily inspired by abstract expressionist Jasper Johns, uses flags and other nationalist symbols to critique and portray her relationship with civil religion. Artists such as Benjamin and Johns choose to use the flag in their work, given its undeniable familiarity. As was widespread among many pop artists, Jasper Johns wanted to take something familiar to Americans and reconstruct it as a means of reimagining it. For example, Jasper Johns’ famous piece Three Flags is faded, rough, and coarse, forcing the observer to analyze not what the flag is but what the flag represents. Johns reclaims the flag, taking it out of its natural habitat and placing it in an art museum. Johns’ work with national symbols has been perceived as protesting 20th-century nativism, questioning the American ideal of ‘liberty,’ and criticizing McArthyism (Seed, 2017). While the work of other American artists, like Childe Hassam, displays proud, waving flags to evoke nationalism in the early 20th century and gain support for the allies’ cause in WW1. Hassam seeks to protect ‘American values’ through national symbols by establishing social Darwinism and excluding immigrants (Broun, 48). His paintings now hang in the White House. However, Johns’ flags are stiff and indifferent- perhaps criticizing the same nationalism displayed forty years earlier. Over time, similar artists have used these nationalist symbols as shorthand to express the complex relationship between patriotism, religion, and the self. Flags establish boundaries, creating and reaffirming national identities.

In the case of Benjamin’s work, the flag serves as a canvas on which she can chart out her experiences- navigating, critiquing, and embracing her relationship with the United States. Where Hassam’s colorful, draping flags display a particular inclusive patriotism, Benjamin’s and Johns’ distorted flags display a highly exclusive nationalism (Morgan, 221). The way flags represent nationality results from a social convention that is widely agreed upon, with each symbol standing for certain concepts such as liberty, justice, and charity (Stuart Hall on Representation). However, nationalist symbols may also stand for formidable concepts such as violence, alienation, and inequality for someone deemed ”Other.” Benjamin’s use of national symbols is intentionally dialectical; as she reinterprets the flag, she causes the observer to question, “How does my relationship to nationalism affect other people?” and “What about America should make me feel patriotic or proud?” Combining images with nationalist and religious symbols allows Benjamin to highlight how this association affects ideas of belonging, homecoming, acceptance, and exclusion.

Sources

Angrosino, Michael. “Civil Religion Redux.” Anthropological Quarterly 75, no. 2 (2002): 239–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3318260.

Broun, Elizabeth. “Childe Hassam’s America.” American Art 13, no. 3 (1999): 33–57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3109339.

Geertz, Clifford. Essay. In Religion as a Cultural System, 5, 2001.

Grace Y. Kao, and Jerome E. Copulsky. “The Pledge of Allegiance and the Meanings and Limits of Civil Religion.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 75, no. 1 (2007): 121–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4139842.

Hall, Stuart. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage, 2013.

Morgan, David. The Sacred Gaze: Religious Visual Culture in Theory and Practice. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Seed, John. “What Does a Jasper Johns Flag Stand for?” HuffPost. HuffPost, July 10, 2017. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/what-does-a-jasper-johns-flag-stand-for_b_59591fb3e4b0f078efd98adf. (Accessed March 17, 2022).