Samantha Baskind • Professor of Art History, Cleveland State

Siona Benjamin has been making intricately detailed, transnational art with a feminist, Jewish, and political bent for almost two decades. She paints the joys, passions, and anguish of both time-honored and unfairly reviled women in the Hebrew canon, from Sarah to Vashti and, most often, Lilith—using gouache, acrylic, gold leaf, and other media. Yes, these women have found representation through the ages; by male artists for centuries, and more recently by female artists, whose opportunities in the field have expanded greatly in the modern era. Benjamin is the beneficiary of a twenty-first century art world that has opened up (to a degree) to non-white male perspectives.

Several aspects of Benjamin’s identity inform her artistic perspective but perhaps most salient is her especially distinct and unusual heritage: Benjamin is descended from the Bene Israel Jewish community whose lore dates them in Asia for 2,000 years. In predominantly Muslim and Hindu India, Benjamin was educated at Catholic and Zoroastrian schools, and at home lived as an observant Jew. Since emigrating from Mumbai to the United States in 1986, arriving in her mid-twenties, Benjamin has been pondering the meaning of belonging in her adopted homeland from all five of her identity markers: South Asian, immigrant, American, woman, and Jew. Her personal story informs her work alongside, and intertwined with, commentary on the imperfect state of the world today. By looking at the five works of art in this exhibition that feature Lilith, one can see how global and personal crises fuel Benjamin’s artistic muse, specifically from a feminist perspective.

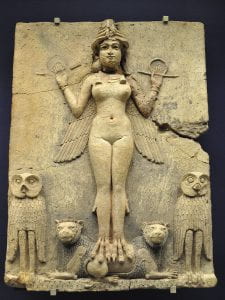

Like Jewish American artists from the previous generation, Audrey Flack and Nancy Spero to name just two, Benjamin feels that scripture can convey some of her feminist sensibilities. For Benjamin, and most feminists who have adopted (or adapted) Lilith in art or literature, the mythological first wife of Adam stands as an icon of independence and courage. Initially appearing in the Babylonian Talmud, Lilith has metamorphosed over the years from a dissatisfied wife who longed for equality with her husband in Eden, and was cast out for it, into a demon who seduces sleeping men, endangers women in childbirth, and kills infants. All this for her so-called insubordination? For being an ancient egalitarian?

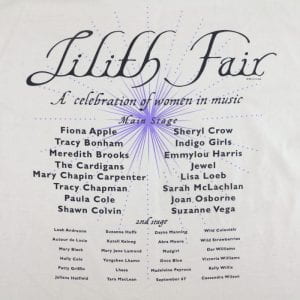

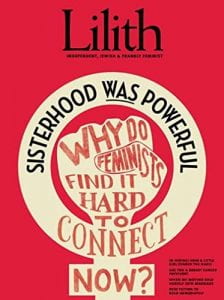

Men traditionally disparaged Lilith because she rebelled against Adam, refusing subservience to him, whereas women have celebrated her stance. Take two literary examples. George MacDonald’s late nineteenth-century novel Lilith negatively characterizes the protagonist as seen through Adam’s eyes: “[Lilith] counted it slavery to be one with me, and bear children for Him who gave her being. . . . Vilest of God’s creatures, she lives by the blood and lives and souls of men.” By contrast, Enid Dame, who wrote poems from a feminist standpoint and in the voice of female biblical figures, assumed Lilith’s point of view on more than one occasion. Dame’s moving poem, from 1999, expresses Lilith’s reasoning, legacy, and regrets in a few short stanzas. The last stanza reads: “sometimes / I cry in the bathroom / remembering Eden / and the man and the god / I couldn’t live with.”  Benjamin, along with the abortion supporting Lilith Fund in Texas, the 90s female-driven music festival Lilith Fair, and the feminist Jewish magazine Lilith published since 1976, are only some of the contemporary artists and activists who have followed Enid Dame in proudly reclaiming Lilith’s perspective.

Benjamin, along with the abortion supporting Lilith Fund in Texas, the 90s female-driven music festival Lilith Fair, and the feminist Jewish magazine Lilith published since 1976, are only some of the contemporary artists and activists who have followed Enid Dame in proudly reclaiming Lilith’s perspective.

Benjamin’s depictions of Lilith are intriguing in their variety, despite their ubiquity in her art. Mingling styles derived from comic books, Pop art, Bollywood, Indian folk imagery, Persian miniatures, and Hebrew illuminated manuscripts, Benjamin elucidates far-reaching issues through reinterpretations that connect women from the Hebrew Bible and Jewish myth—Lilith most consistently—to the present day. The ambiguous Lilith, wrongly cast as an outsider, allows Benjamin to grapple with world diversity and injustice. As she explains: “I can dip into my own personal specifics and universalize, thus playing the role of an artist and activist.”

Benjamin’s depictions of Lilith are intriguing in their variety, despite their ubiquity in her art. Mingling styles derived from comic books, Pop art, Bollywood, Indian folk imagery, Persian miniatures, and Hebrew illuminated manuscripts, Benjamin elucidates far-reaching issues through reinterpretations that connect women from the Hebrew Bible and Jewish myth—Lilith most consistently—to the present day. The ambiguous Lilith, wrongly cast as an outsider, allows Benjamin to grapple with world diversity and injustice. As she explains: “I can dip into my own personal specifics and universalize, thus playing the role of an artist and activist.”

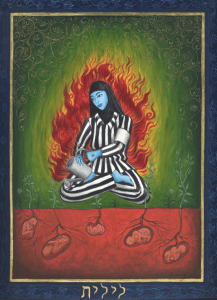

All of Benjamin’s Liliths have vibrant, turquoise blue skin, just as all of her women are colored blue. “Blue like me” is Benjamin’s calling card. “Being blue is a symbol of being other,” she says. Blue is the signature color of a woman of color, like Benjamin herself. She favors blue because it signals the sky and the ocean. Benjamin’s figures also assume the blue flesh traditionally used in depictions of the Hindu deity Krishna.

The Finding Home series is Benjamin’s largest and on which she has been working intermittently since the 1990s. Subtitled Fereshteh (“angels” in Urdu), the series comprises 82 small scale paintings that explore the nature of place, both “spiritually and literally,” as Benjamin puts it. Twelve paintings from the series include Lilith.

The 68th installment of the Finding Home series (2005) suggests Lilith’s multivalent identities. Unafraid to take on controversial topics, Benjamin portrays Lilith—so indicated by her name delicately inscribed in Hebrew on the decorative painted frame—as both a Holocaust survivor and Palestinian refugee. Rendered on a tiny, fragile piece of paper, demonstrative of her especially fragile status in this particular composition, Lilith sits cross-legged at center. Surrounded by dangerous fire, striking against verdant green, she wears the uniform of a concentration camp inmate and an armband, but also a Muslim veil, and with the tell-tale sign of Christian martyrdom: stigmata on her left hand. Notably, that armband has been left blank, a reminder of the world’s many oppressed – not only women, not only Jews, not only Palestinians. Unable to find hope for the ever-despised Lilith, Benjamin has her tending saplings that will not grow. They are, Benjamin explains, not rooted to the earth in life, but “buried from yesterday’s wars and tomorrow’s plunderings.”

The 68th installment of the Finding Home series (2005) suggests Lilith’s multivalent identities. Unafraid to take on controversial topics, Benjamin portrays Lilith—so indicated by her name delicately inscribed in Hebrew on the decorative painted frame—as both a Holocaust survivor and Palestinian refugee. Rendered on a tiny, fragile piece of paper, demonstrative of her especially fragile status in this particular composition, Lilith sits cross-legged at center. Surrounded by dangerous fire, striking against verdant green, she wears the uniform of a concentration camp inmate and an armband, but also a Muslim veil, and with the tell-tale sign of Christian martyrdom: stigmata on her left hand. Notably, that armband has been left blank, a reminder of the world’s many oppressed – not only women, not only Jews, not only Palestinians. Unable to find hope for the ever-despised Lilith, Benjamin has her tending saplings that will not grow. They are, Benjamin explains, not rooted to the earth in life, but “buried from yesterday’s wars and tomorrow’s plunderings.”

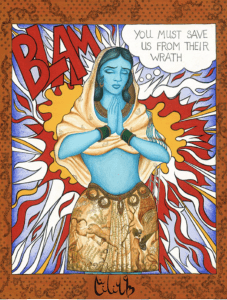

Finding Home #80 (2006) is inspired by the Amar Chitra Katha comics of her youth and two Christian sources: Gian Lorezo Bernini’s seventeenth-century sculpture Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, and imagery associated with Saint Sebastian. Painted many times over the centuries, St. Sebastian was martyred by arrows. Finding Home #80, and others, are influenced by what Benjamin deems her “personal mythology” derived from the belief systems of her youth: Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. Here Lilith crosses religious boundaries: donning a tallis (Jewish prayer shawl), wearing a hamsa (amulet in both Jewish and Muslim traditions), and impaled by a weapon. Lilith’s name appears in Hindi at the painting’s base.

Finding Home #80 (2006) is inspired by the Amar Chitra Katha comics of her youth and two Christian sources: Gian Lorezo Bernini’s seventeenth-century sculpture Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, and imagery associated with Saint Sebastian. Painted many times over the centuries, St. Sebastian was martyred by arrows. Finding Home #80, and others, are influenced by what Benjamin deems her “personal mythology” derived from the belief systems of her youth: Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. Here Lilith crosses religious boundaries: donning a tallis (Jewish prayer shawl), wearing a hamsa (amulet in both Jewish and Muslim traditions), and impaled by a weapon. Lilith’s name appears in Hindi at the painting’s base.

Yet this suffering Lilith will not stand idly by. An arrow of war may pierce her, but she has not come unprepared to battle. Damned and vilified through the ages, Lilith is now empowered with a cowboy’s gun and holster dangling at her waist. She may die from her wound amid plumes of bold red flames set against a faultless blue background, but she will perish blissfully – in ecstasy like her predecessor St. Teresa – and in the strength of her convictions. Her head turns upward toward the heavens and the stars of the sky. A dove leads her to a place devoid of intolerance and strife.

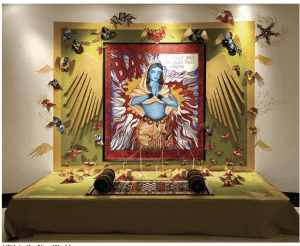

“Lilith in the New World” Installation

Lilith in the New World (2008), a multimedia installation, recalls a theatrical stage (Benjamin has a master’s degree in theater set design). With Lilith in the New World, Benjamin moved from the tiny, delicate paintings that mostly characterized her art to this point. At center hangs a large reproduction of her 2005 Finding Home #75: Lilith, a visual play in color and style on Roy Lichtenstein’s 1962 iconic Pop art canvas Blam!. Benjamin copies the blaze triggered by the exploding aircraft in her predecessor’s well-known canvas but features a blue-skinned Lilith rather than a doomed plane. Oversized gold wings made of wood frame the painting, and more than two dozen tiny blue dancers, all hand painted by Benjamin, surround the installation. Other blue dancers occupy the base.

Detail, Lilith in the New World

In front of this dramatic arrangement, sits a chess set on a Persian rug. The chess set symbolizes war, further connecting the canvas to Lichtenstein’s, but while he glorifies combat, Benjamin condemns war. She firmly believes that it is pointless to play “chess,” her metaphor for war. This tactical game of wits with pawns and rooks on a board translates to physical combat with men and women on the battlefield. Such continued violence indicates that the new world is really not new at all.

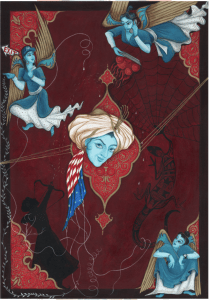

More modest in size and highly vertical, Finding Home #87 (2008) pictures the head of a turban-wearing Lilith. When conceptualizing this work, Benjamin harkened back to memories of her great-grandfather, an observant Jew who wore a turban in his native land. Yet the sash hanging from the turban adds an unexpected dimension, for it is painted in the colors of the American flag and adorned with tzitzit (fringes), which typically hang from a tallis. In this instance, Lilith has become a conduit for Benjamin to comment on the duality of her Jewish American immigrant experience. So too, the ornamental emblem behind Lilith deliberately Orientalizes the mischievous, smiling rebel, an artistic ploy on Benjamin’s part to make her appear more exotic. In doing so, Benjamin also addresses race and her perpetual sense of difference – a lived experience of Americans’ tendency to fetish the Other.

As the legend goes, three angels were sent by God to retrieve Adam’s errant wife, who entered the Red Sea following her exit from the Garden of Eden. As pictured by Benjamin, those angels are not wrathful but playful: One wears a Yankees cap ready to go to a ballgame if Lilith would get it in gear; another casually sits in the corner, hoping that Lilith will hurry up already; and a third, on her cell phone with God, reports that Lilith has no intention of returning to “paradise.”

The three-paneled format that Benjamin appropriates for Lilith’s Lair and Other Stories of Deception (2011), a triptych, is decidedly not Jewish. In the history of art, triptychs were commonly employed during the medieval era and Renaissance for altarpieces, and are a staple of Christian art. Benjamin, though, has imbued the richly red hued, five-foot wide triptych with a multicultural stamp. A radiant cerulean Lilith appears at center with a gold halo, another Christian reference, surrounding her entire head. Eight photo-collaged blue dancers, recurrent figures in her art, sit atop that halo. Others decorate the four ornate corners of the central panel. Just as the side panels of Christian altarpieces open and close, so does this work.

At the bottom of the central panel, Benjamin has imagined Lilith entering the Red Sea. Under the sea, Lilith is finally a woman free to create a paradise of her own making. The dancers trailing behind rejoice in her liberation. Atop the right wing, Lilith carries her suitcase to begin her new, independent life. In front of this altar of sorts, Benjamin has placed a blue cast of the lower half of her face as an offering.

Benjamin views Lilith as her inspiration: “I have become Lilith and Lilith has become me.” Lilith is the ancient woman who asked questions and stood up for her convictions, and as such, she serves as Benjamin’s ideal.