By Hemangi Patel

Exhibition Pieces Drawing on Indian and Persian Miniatures

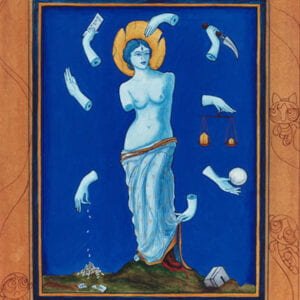

Exodus #1 14″ x 10″ Gouache and mixed media on museum board mounted on wood panel 2016

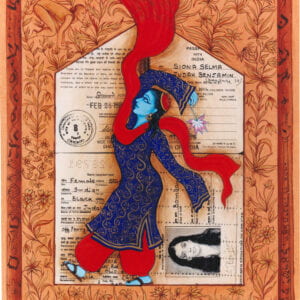

Siona Benjamin – Fulbright Series #8 Hannah (Munmun) Emanuel Samuel (Pezarkar) 35″ x 35″ Photo-collages with gouache and acrylic paint on Hahnemuhle paper 2012-2013

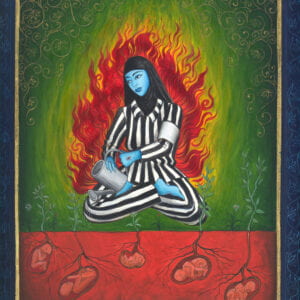

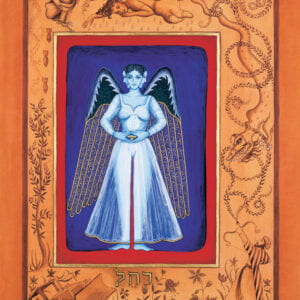

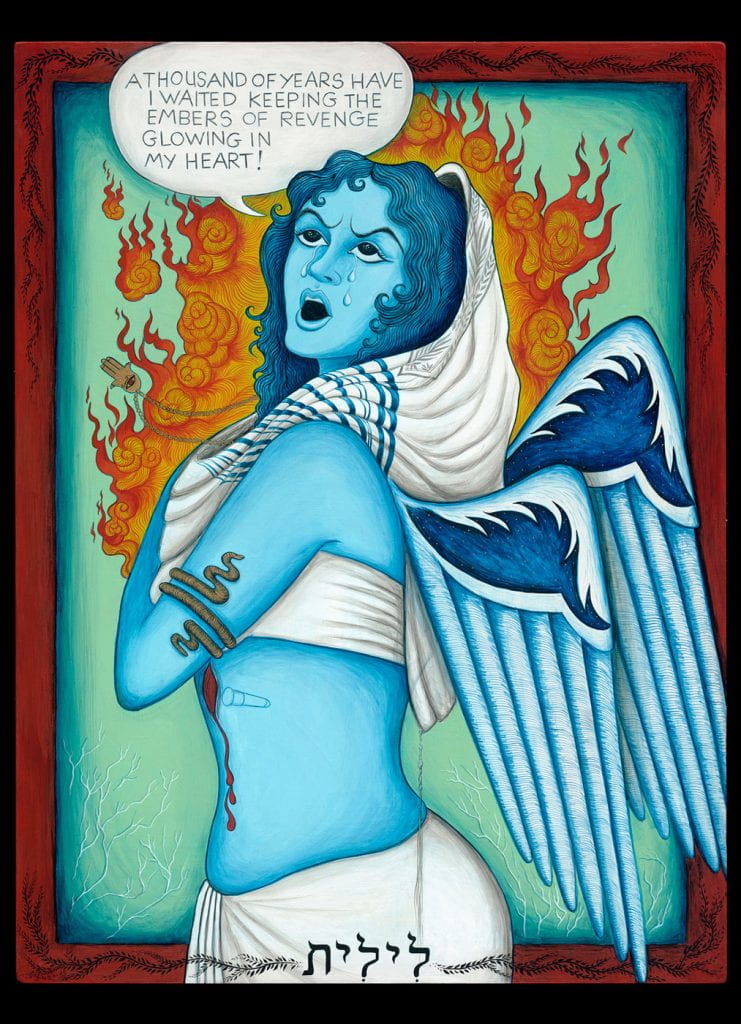

Siona Benjamin – Finding Home #74 (Fereshteh) “Lilith” 30″ x 24″ Gouache on wood panel 2006

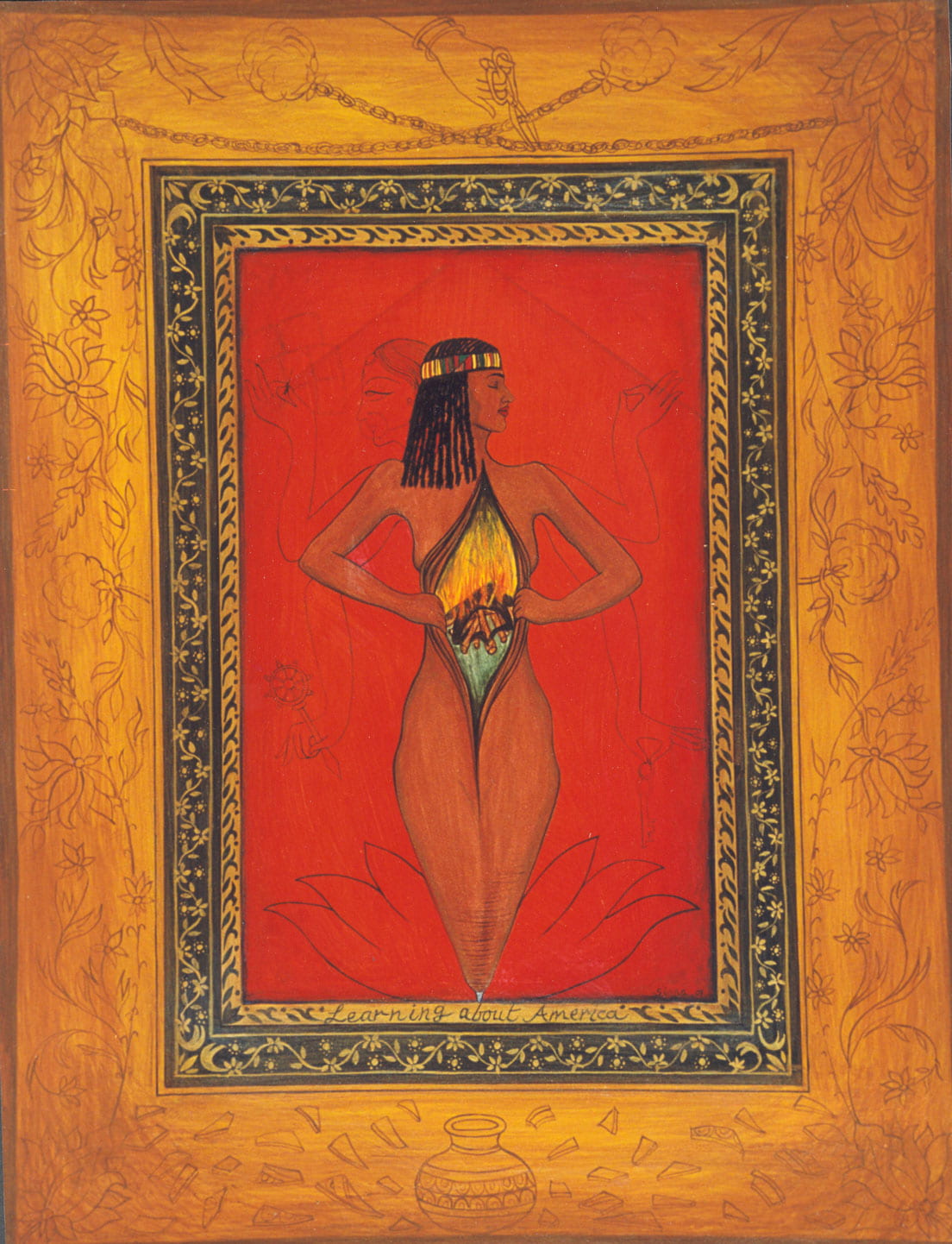

Siona Benjamin – Four Mothers Who Entered Pardes Installation; Four works each 6 feet tall x 3 feet wide; Hand embellished and archival prints on canvas 2014

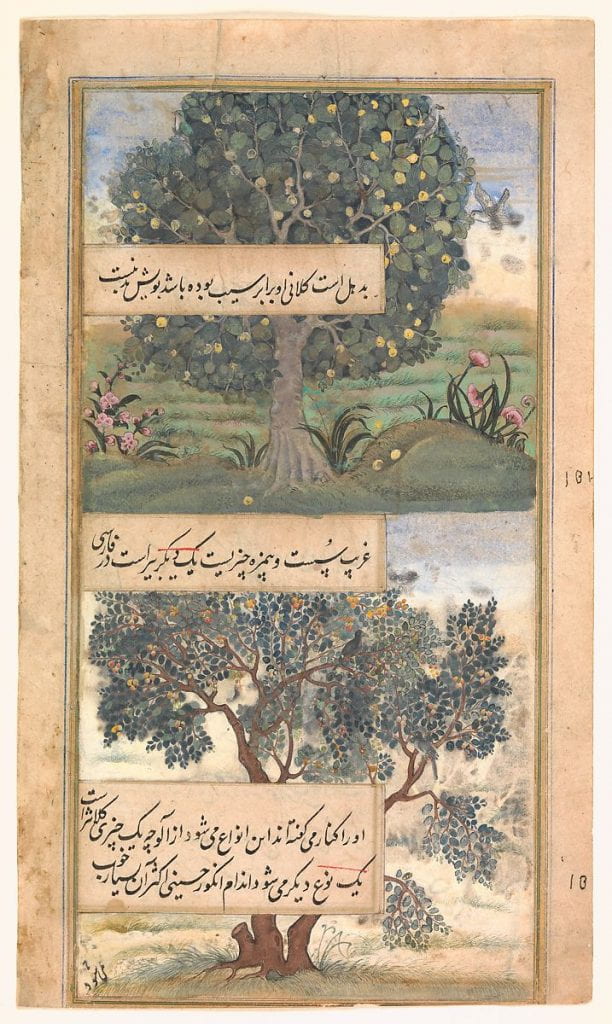

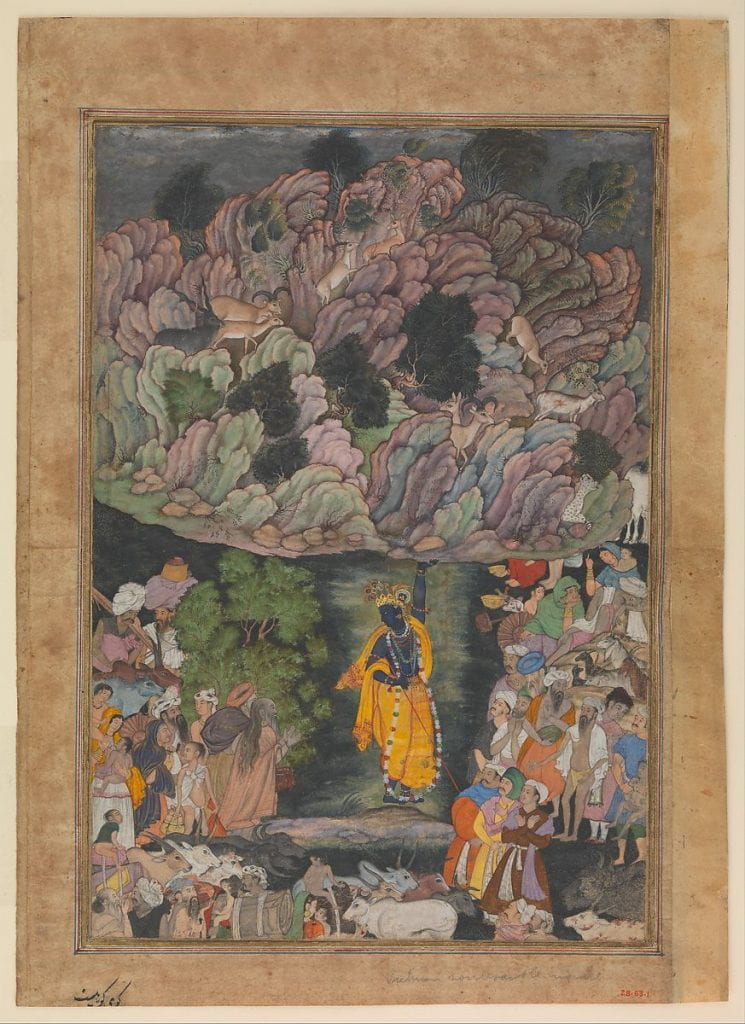

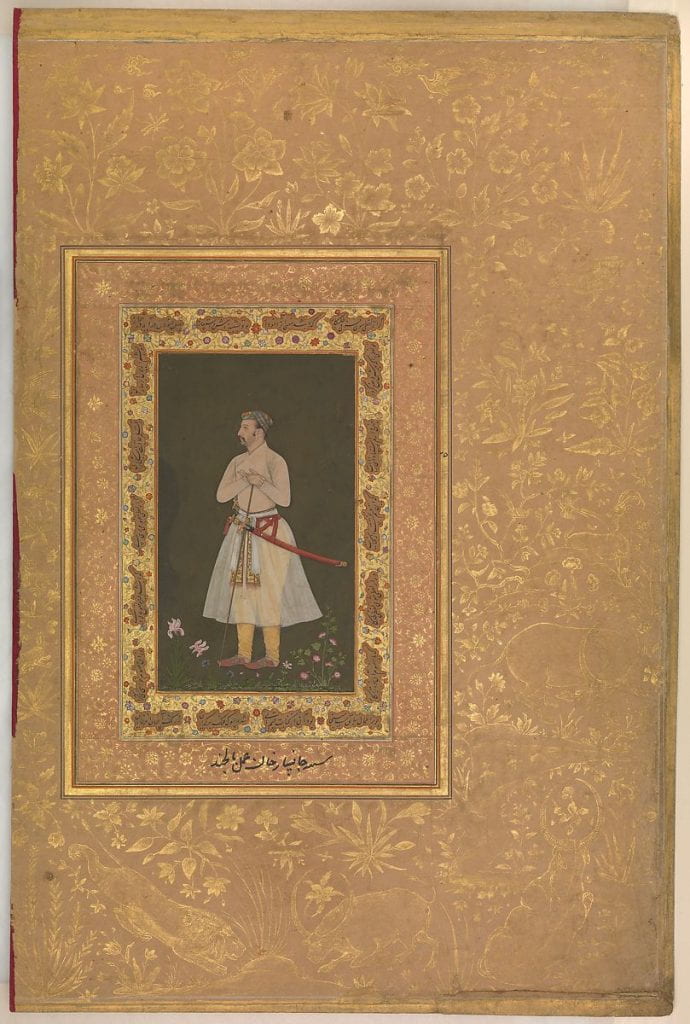

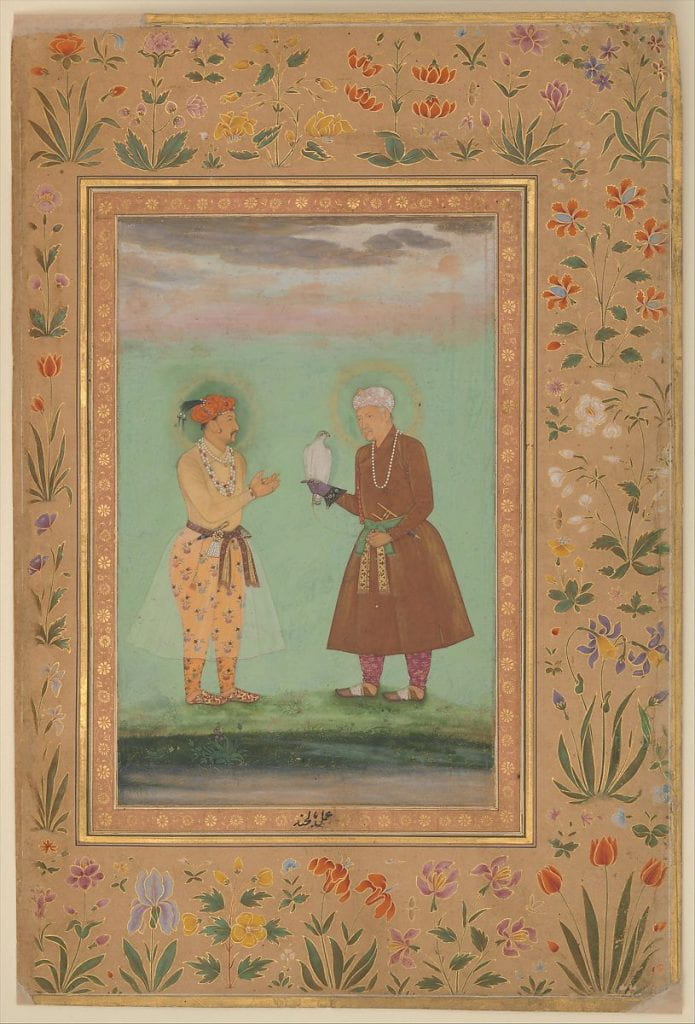

Examples of Persian and Indian Miniatures

Persian Miniatures pictures above from the Metropolitan Museum of Art Collection

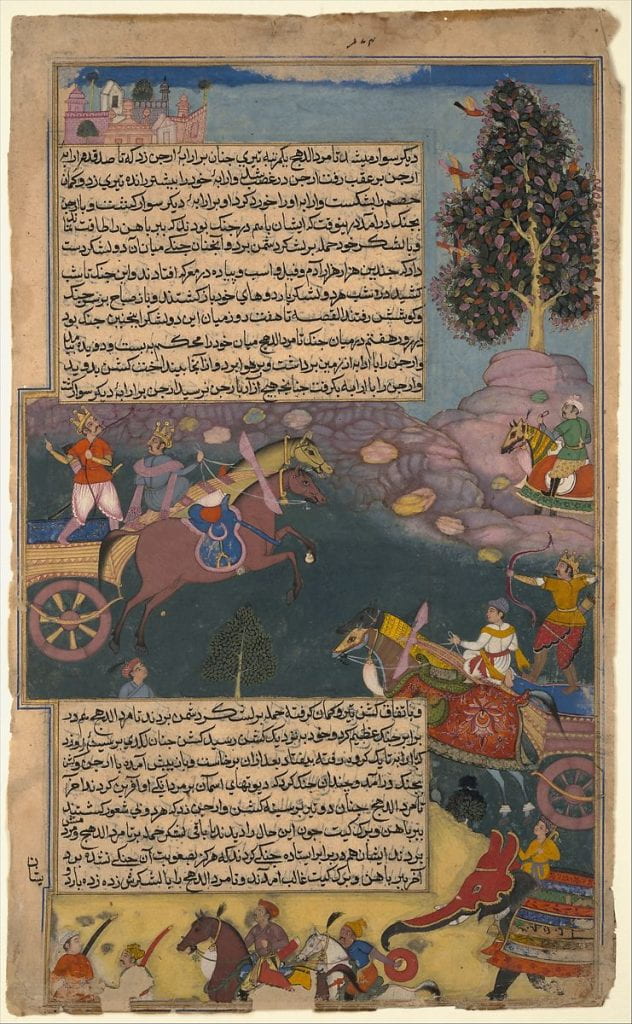

(1) Title: “Arjuna Battles Raja Tamradhvaja”, Folio from a Razmnama

Patron: ‘Abd al-Rahim ibn Muhammad Bairam Khan Khan-i Khanan (Indian, Delhi 1556–1627 Agra)

Date: ca. 1616–17

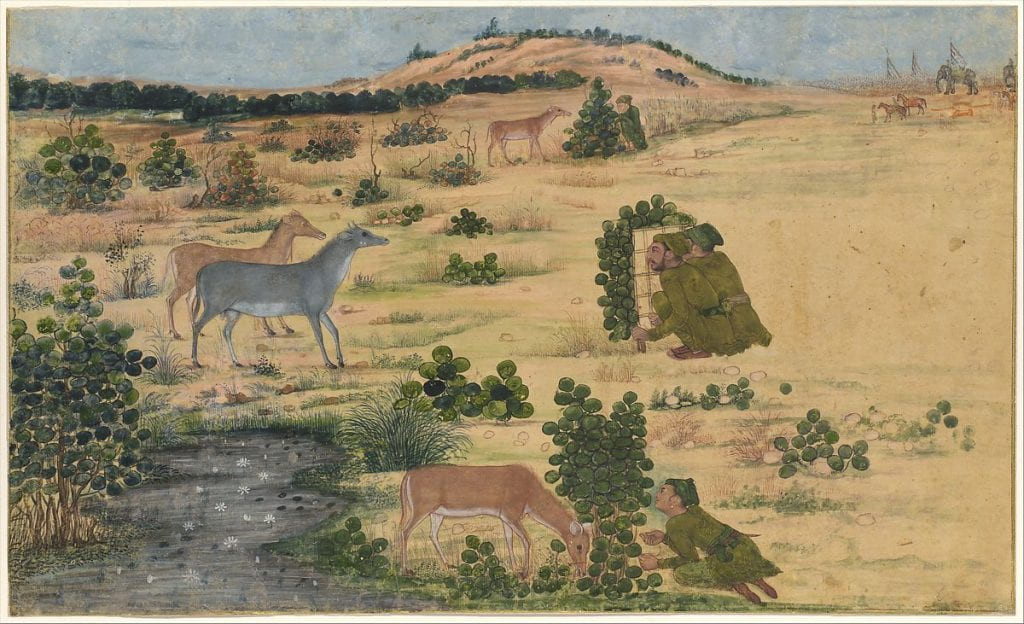

(2) Title: Preparations for a Hunt

Date: ca. 1680

(3) Title: “Three Trees of India”, Folio from a Baburnama (Autobiography of Babur)

Date: late 16th century

(4) Title: “Krishna Holds Up Mount Govardhan to Shelter the Villagers of Braj”, Folio from a Harivamsa (The Legend of Hari (Krishna), Date: ca. 1590–95

(5) Title: “Portrait of Jahangir Beg, Jansipar Khan”, Folio from the Shah Jahan Album

Artist: Painting by Balchand (Indian, 1595–ca. 1650)

Calligrapher: Mir ‘Ali Haravi (died ca. 1550)

Date: verso: ca. 1627; recto: ca. 1530–50

(6) Title: “Jahangir and his Father, Akbar”, Folio from the Shah Jahan Album

Artist: Painting by Balachand (active 1595–ca. 1650)

Calligrapher: Mir ‘Ali Haravi (died ca. 1550)

Date: verso: ca. 1630; recto: ca.1540–50

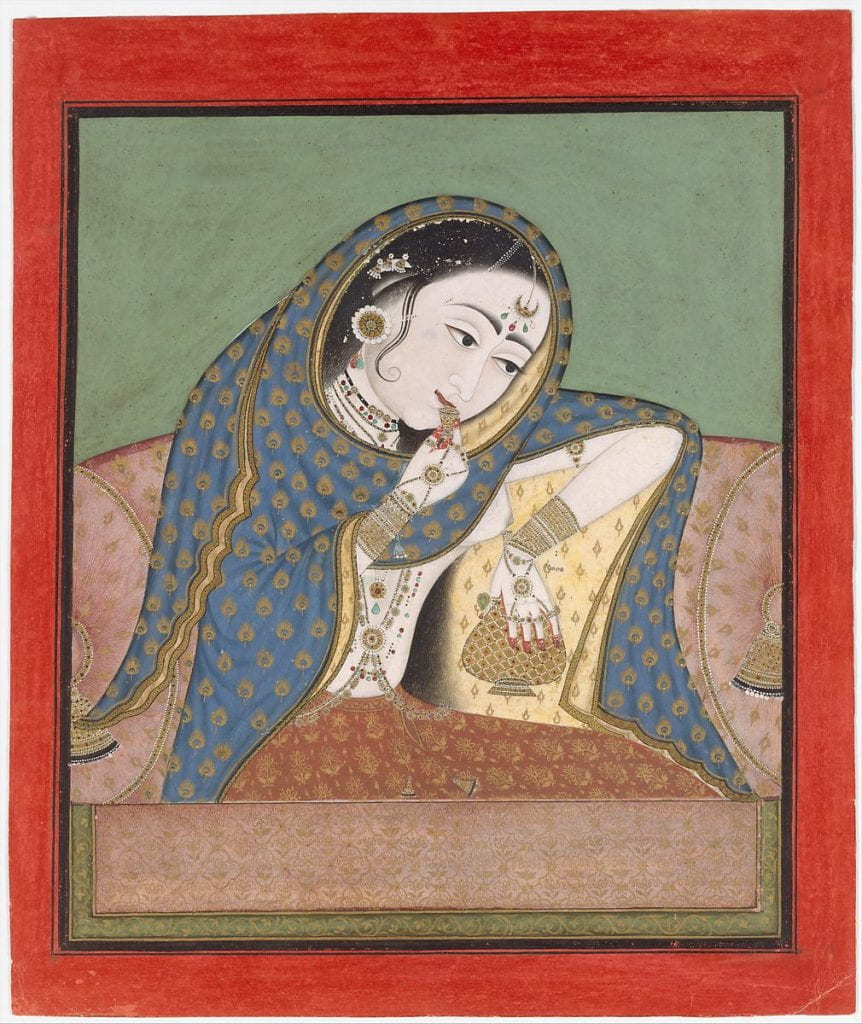

(7) Title: Melancholy Courtesan

Date: ca. 1750

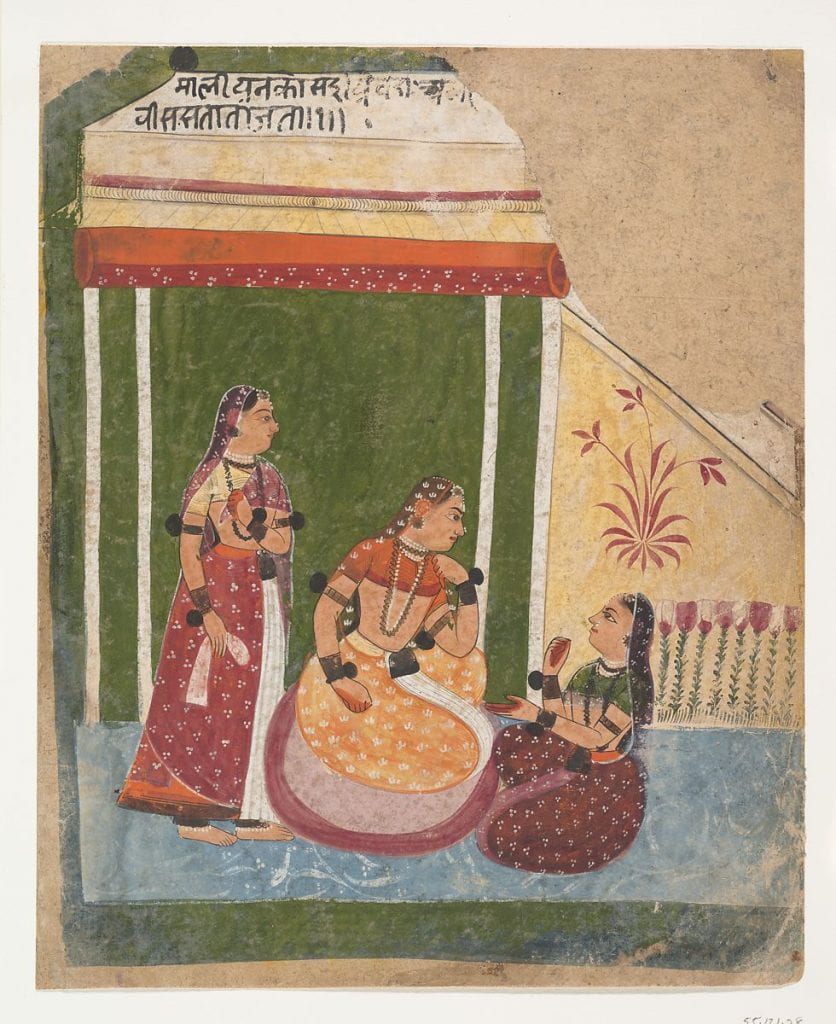

(8) Title: Ladies in a Pavilion: Page from a Dispersed Ragamala Series (Garland of Musical Modes)

Date: ca. 1640–50

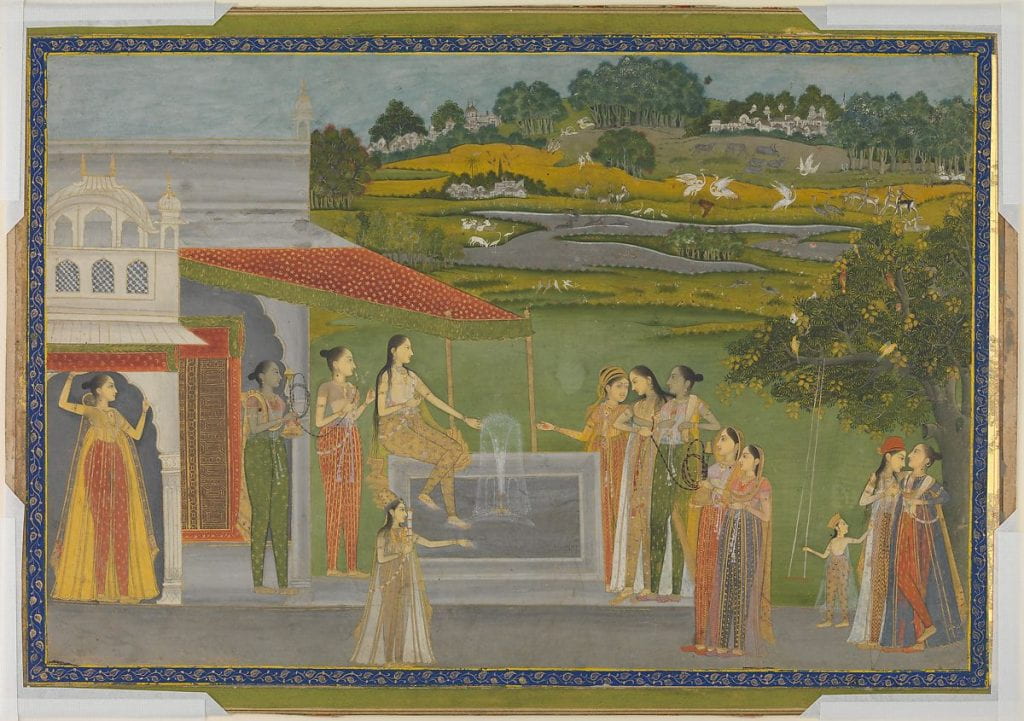

(9) Title: Princesses Gather at a Fountain

Date: ca. 1770

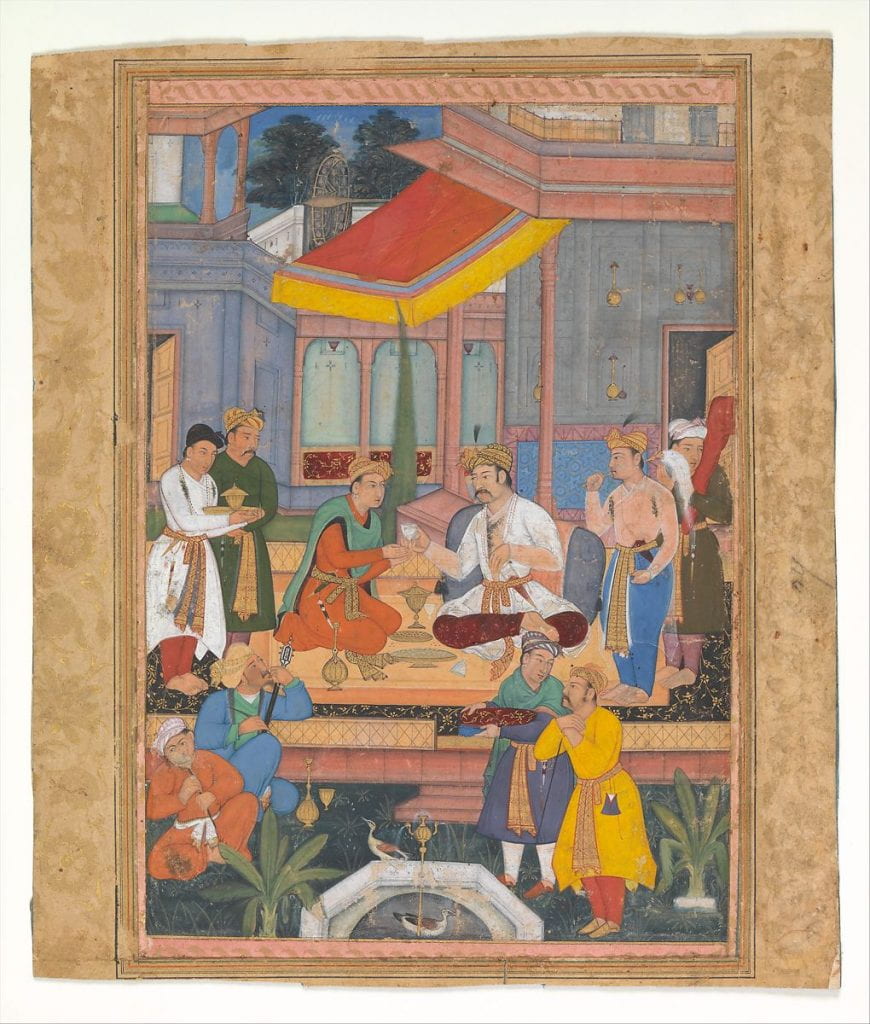

(10) Title: Interior of a Courtyard with Figures

Date: early 17th century

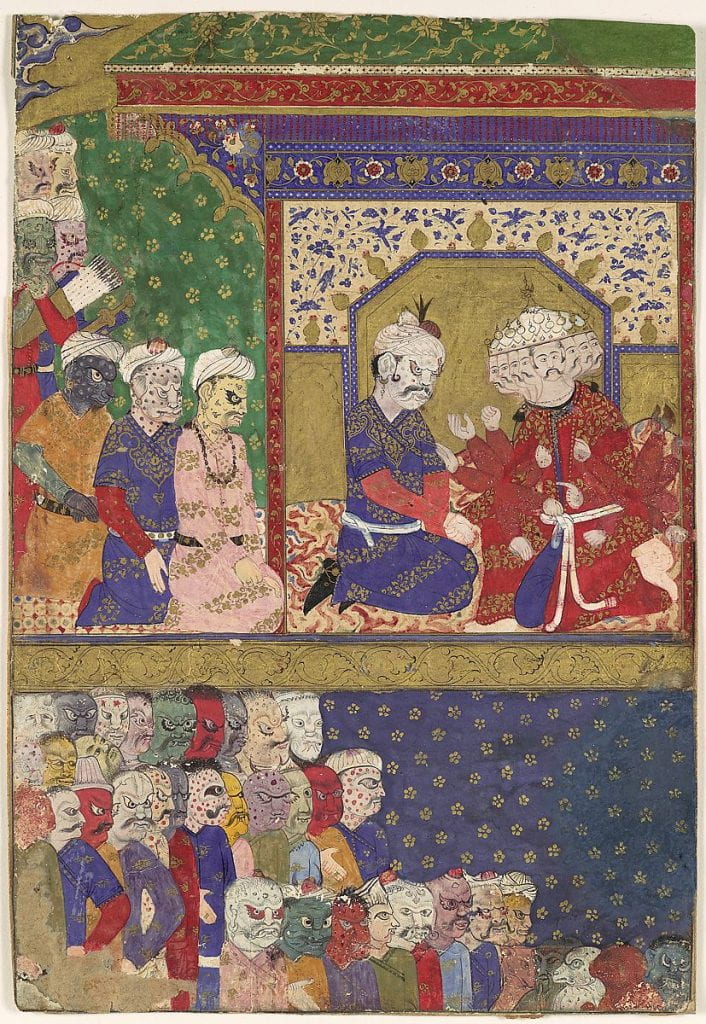

(11) Title: “The Court of Ravana”, Folio from a Ramayana

Date: ca. 1605

(12) Title: Lion at Rest

Date: ca. 1585

Additional Works by Siona Benjamin Inspired by Indian and Persian Miniatures

Gallery Talk

Transcript

Siona Benjamin draws on a wide range of artistic genres in her work, meshing them together to form her unique style. This hybrid artistic approach reflects her own identity: Bene Israel Jew, Indian, American, woman, and immigrant. Through her pieces, Benjamin pushes the audience to question “how Jewish art should be defined,” while also bringing awareness to complex experiences of belonging, identity, and marginalization that many immigrants wrestle with (Greenberg et al., 6). By centering female figures, her work is also a response to the exclusion of female voices within a male dominated world. Indian and Persian miniature paintings are among the many art forms that inspire her work. In particular, she borrows from the style of miniature painting that originated in the Mughal empire between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. Through her unique take on this art form, Benjamin illustrates the faces and stories of refugees and the Bene Israel Jews, displays her journey in finding home “nowhere and everywhere,” and retells male dominated stories with female characters and a modern feminist gaze (Greenberg et al., 6, 13).

The “Exodus” series by Siona Benjamin is inspired by the concept of Paradise. Through this collection, she illustrates the stories of refugees who have been displaced from their homes and “[roam] the world in a constant search for their lost paradise…[or] for a new one” (Siona Benjamin, Exodus: I See Myself in You). The pieces in this series raise the question of “why humans pursue and strive for perfection and paradise” and the lengths they will go to attain it (Siona Benjamin, Exodus: I See Myself in You). Benjamin utilizes many stylistic features of the traditional miniature style in this series. For example, Exodus #1 is a 14 inch by 10 inch painting of a woman with a headcovering and angel wings. It is surrounded by a colorful blue and pink marbled border containing images of flowers and birds. This size and border style is similar to the miniature paintings that originated during the reign of the Mughal empire. For example, two paintings by Balchand from the Shah Jahan album titled “Portrait of Jahangir Beg, Jansipar Khan” and “Jahangir and his Father, Akbar” both measure 15 3/8 inches by 10 3/8 inches and are surrounded by a heavily decorated gold border that includes imagery of flora and fauna (Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Although the oldest known miniatures are those that originated from Egypt during the second-century B.C.E., there are very few artifacts from this time period due to the lack of well preserved papyrus. The art style of miniature paintings became popularized during the Middle Ages and was spread to Middle Asia by Mani, an Iranian prophet who founded Manichaeism. This art form was then conveyed by the Turks to China and Persia and eventually to Europe (Karakas and Rukanci, 1). Historically, miniature paintings served to illustrate important events and celebrate figures, such as battles, kings, and deities, whether these pieces were standalone or part of a larger collection. For example, sixteenth century Mughal paintings often depicted the founder of the Mughal empire, Babur, and his adventures, revealing to the audience his personality, exploits, and observations from his journeys (Vaishnavi and Ramya, 18). Emperors or aristocrats would often sponsor artists to illustrate manuscripts, leading to the creation of volumes that contained alternating pages of calligraphy and illustrations (Soucek, 167). One important patron of such endeavors was Emperor Jahangir, who had several portraits and depictions of nature included within his autobiography. Jahangir was heavily influenced by European painting. Under his guidance, the style of miniature paintings shifted from the traditional flattened, multi-layered style to a single point perspective, giving the paintings a more three-dimensional view (Vaishnavi and Ramya, 20).

Benjamin utilizes the storytelling feature of miniature paintings to showcase the stories of the Bene Israel community through her “Fulbright Art Series” collection. This series served to “raise awareness about the long-standing history of the Indian Jewish communities in India,” particularly in response to the series of terrorist attacks that occurred in Mumbai on November 26 to 29, 2008 by Lashkar-e-Taiba, an Islamist terrorist organization from Pakistan (Siona Benjamin, Fulbright Series). The places attacked include the Chhatrapati Shivaji railway station, the Leopold Café, the Oberoi Trident Hotel, the Taj Mahal Palace and Tower Hotel, the Cama and Albless Hospital, the Metro Cinema, and the Chabad House, resulting in a total death toll of 174 people, including 20 security force personnel, 9 attackers, and 26 foreign nationals, and 304 injured people (D’Souza). Jews were specifically targeted when the Chabad house—a Jewish outreach center, synagogue, and hostel—was attacked, resulting in the death of six of its occupants, including the Rabbi and his wife. Benjamin’s Fulbright art pieces employ the framing technique displayed in Mughal miniature paintings. However, instead of using a traditional square style gold leaf border, Benjamin uses photo collages to create the appearance of a frame. For instance, Fulbright series #8 depicts Hannah Emanuel Samuel, a Bene Israel chef who everyone calls Munmun. Benjamin uses a plate of various Jewish and Indian delicacies, a portable gasoline stove with a pot full of food placed on top, and delicate red flame decorations to form a frame around Hannah, who is depicted with many arms holding plates to resemble a menorah. Deities of the Hindu pantheon are also often depicted with multiple arms containing various items, including weapons and musical instruments. The presence of multiple arms serves as a symbol for their divinity and phenomenal power. By depicting Hannah with eight arms, Benjamin aims to represent the various responsibilities and roles women are often expected to juggle. Benjamin incorporates Jahangir’s single point perspective style by placing Hannah behind the giant pot, which is behind the red flames. This overlap gives the painting a three-dimensional look. Benjamin also incorporates a symbolic olfactory element into this painting by mixing turmeric spice into the paint. This stylistic choice not only enhances the color of the background but also illustrates the importance of Hannah’s cooking to herself and her community.

Another notable patron of traditional miniature paintings was Emperor Akbar. Under his guidance, the painting style became more developed and nuanced. Miniature paintings began to take on a landscape scheme, in which the picture would be divided into different levels, often with a birds eye view. Instead of being overlapped, figures were understood to be behind or in front of one another (Kramrisch, 14). Large emphasis was placed on the detail of expressions, gestures, and tones of figures (Ghosh, 31). The background would typically be painted in lighter colors, while figures were painted in darker or brighter colors to accentuate them (Vaishnavi and Ramya, 21-22). Heavily decorated borders often containing gold leaf and flora and fauna would frame paintings (Soucek, 167). During his rule, Akbar created one of the most significant ateliers of this time period (Ghosh, 29). With the assistance of two notable Persian masters, Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd as-Samad, Akbar funded and guided the creation of the 1,400 illustrations that comprise the Hamzanama—a collection of stories about Hamza ibn Abdul-Muttalib, an uncle of Muhammad. Within these paintings, the figures were often scaled up in size to fill up space. This helped draw the eye of the viewer to not only the body language and emotions of the figures but also the details of their clothing and setting (Kramrisch, 15-16).

Emperor Akbar was notable for his implementation of Sulh-i-kull, an Arabic term meaning “peace with all,” with the aid of Abu al-Fazl ibn Mubarak, his courtier and biographer (Kinra, 137). Akbar believed that it was the duty of every effective ruler to act “in the best interests of the state” by maintaining social harmony, protecting all his subjects, and ensuring impartiality since emperors were “the shadow of Divinity” (Kinra, 154 and 152). Credited with creating one of the most tolerant and inclusive states in the early modern world through the practice of religious pluralism, or the coexistence of diverse religious beliefs within a society in which each individual has the right, freedom, and safety to worship their religion, Akbar was able to maintain tranquility within his empire. Since a large portion of his subjects were Hindu, Akbar gained the trust of his conquered subjects by implementing policies that enabled his subjects to maintain their way of life and by funding the creation of art and literature that celebrated the religious diversity within his empire. For example, Akbar established the ‘ibādat-khāna, or the House of Faith, Worship, and Devotion, which was located in the capital city of Fathpur Sikri and served as a place of debate and dialogue between followers of different sects (Kinra, 154-155). Additionally, Akbar had the Hindu epics, the Mahabharata and Ramayana, translated into Persian and illustrated by his studio (Kramrisch, 15-16). Collaboration amongst artists was vital in order to accomplish this great undertaking. Usually a master artist would design and sketch the paintings, while apprentices would perform the mechanical task of putting on the color (Ghosh, 31). By encouraging discussion between different religions and by illustrating Hindu devotional texts, Akbar honored and shared the cultures of those he ruled. Akbar’s pluralism did not only aim to foster acceptance of Hinduism or other non-Muslim religions, such as Jainism and Sikhism, but also cultivated civility amongst different Islamic communities, such as Sunnis and Shiites and Turks, Afghans, and Persians (Kinra, 149). In addition, scenes from other Hindu devotional texts, such as the Bhagavata Purana and the Gitagovinda were depicted in a series of miniature paintings. This illustrates one of many ways that artistic enterprises became the means for inter-religious and intercultural cross-fertilization and collaboration. Benjamin draws from this long standing history of intercultural and inter-religious exchange within the Indian subcontinent in her work.

In her Finding Home series, Benjamin raises the questions of identity and the definition of “home” in the context of immigration. Finding Home #74 depicts the hallmark framing technique through the use of a dark red frame decorated with floral accents and some calligraphy at the bottom. This piece also depicts the large Mughal miniature art influence on Benjamin’s work through the use of the scaled-up, space-filling figure. Similar to how Mughal artists would increase the size of figures in relation to the background to emphasize the figures’ emotions and gestures, Benjamin provides a close up view of the Lilith figure. In doing so, the audience can clearly see the anger and distress the figure is experiencing. Benjamin also surrounds Lilith’s head with background fire details to emulate the depictions of Muhammad in miniature paintings in which his face is often veiled or represented by a flame. In her portrayal, Lilith is angelic, unlike the traditional depictions of her as a she-demon. Benjamin’s feminist reinterpretations of the stories of female figures from the Hebrew Bible and other Jewish legends provides social commentary on the repression of women voices not only in history but also within our current society (Greenberg et al., 6, 16).

Miniature paintings during the Mughal rule not only featured rulers and deities, but also aristocrats and common folk to showcase imperial court and everyday life (Majlis, 307). Themes on women became popularized during Jahangir’s rule due to the influence of Nur Jahan, his wife, and continued throughout Akbar’s rule. Paintings showcasing women often displayed themes of love and romance, beauty, family, and spirituality. These miniatures depicted the lives of both wealthy and poor women engaged in leisure activities or earning their livelihood. For example, royal women were often depicted watching dance and musical performances, drinking wine, playing chess, or riding horses, while their maidens were depicted serving their ladies food, participating in performances, or even laboring in construction sites. Women were often depicted with “sensuous looks and enticing gestures” to emphasize their emotions and the activities in which they were participating (Lavanya, 1665, 1667-1668, 1670). Detailings of their dress and ornaments served as indications of status and also served to display the skill of artists (Majlis, 307). The paints and inks used in these paintings were made from minerals, like cinnabar and copper salts, or biological sources, like insects and cow urine (Lavanya, 1668). In her pieces, Benjamin primarily uses Holbein gouache and a gel medium instead of natural pigments and gum Arabic to build layers of color (Greenberg et al., 57).

Due to European influence, elements of angels and fairies were incorporated into traditional miniatures (Lavanya, 1666). Many of Benjamin’s pieces depict angels with sharp, knife-like wings, which were characteristic of angel wings depicted in Persian miniatures. For instance, the Lilith figure in Finding Home #74 is depicted with wings, further solidifying Benjamin’s angelic portrayal of Lilith. Benjamin’s Four Mothers who Entered Pardes installation also includes angel imagery. This installation retells the story of the four Rabbis that entered paradise by replacing them with the four matriarchs: Sarah, Rebecca, Leah, and Rachel. By feminizing this story, Benjamin emphasizes the important roles of the four mothers within Jewish legends. This “recycling of mythology” is prevalent in Benjamin’s work as she incorporates Jewish and Biblical figures and places them within modern day contexts (Greenberg et al., 36). In doing so, Benjamin is able to foster a connection between the past and the present, showing the audience that there are a lot of lessons to learn from the past.

Sources

D’Souza, Shanthie Mariet. “Mumbai terrorist attacks of 2008.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/event/Mumbai-terrorist-attacks-of-2008.

Ghosh, Sourabh. “Portraiture in Indian Miniature Paintings” Chitrolekha Journal on Art and Design 2, no. 1 (2018): 29-40. https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/cjad.21.v2n103

Greenberg, Elizabeth, Soltes, Ori Z., Baigell, Matthew, and Rosen, Aaron. Siona Benjamin: Beyond Borders. Edited by Elizabeth Greenberg. New York: The Sage Colleges, 2016.

Karakas, H. Sekine, and Rukanci, Fatih. “The Miniature Art in the Manuscripts of the Ottoman period (XVth-XIXth Centuries).” MELCom International 30th Conference (2008). https://www.melcominternational.org/?page_id=160&year=2008

Kinra, Rajeev. “Revisiting the History and Historiography of Mughal Pluralism.” ReOrient 5, no. 2 (2020): 137-182, DOI: 10.13169/reorient.5.2.0137

Kramrisch, Stella. Painted Delight: Indian Paintings from Philadelphia Collections. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1986.

Lavanya, B. “Glimpses of Women in Mughal Miniature Paintings.” International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research 4, no. 3 (2019): 1663-1672. ISSN: 2455-8834

Majlis, Najma Khan. “Representation of Professional and Working Women in Mughal Miniature Painting (16th-18th Century).” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 67 (2006): 307–311. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44147951.

Soucek, Priscilla P. “Persian Artists in Mughal India: Influences and Transformations.” Muqarnas 4 (1987): 166-181. https://doi.org/10.2307/1523102.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://www.metmuseum.org/.

Vaishnavi, P., and Ramya, B. “Mughal Miniature Paintings: An Analysis.” Kristu Jayanti Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 1, no. 2 (2021): 18-24. http://kristujayantijournal.com/index.php/ijss/article/view/2189/1551