Rebecca Fakunle

The Meaning of Roots Gallery Talk

Transcript

Simone Weil wrote, “to be rooted is the most important and least recognized need of the human soul.” It is necessary to rethink the idea of roots and relation to our identity and other forms of our homeland. The metaphorical concept of having roots involves an intimate linkage between people and distinct places. Artists Siona Benjamin and Malik Canty have committed their artwork to portray how we are all rooted in this world. Benjamin’s Finding Home #68 and Finding Home #86, along with Canty’s African Roots piece, express two sides of roots: having a connection to our roots and being displaced and uprooted.

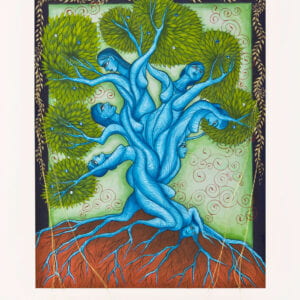

Malik Canty is an artist, writer, and poet from Brooklyn, New York. Canty draws to reveal the messages trapped in his soul and writes as a testimony of the durability of his people. He drew “African Roots” as a way to express how Black people have been dispersed throughout the world and their denial of African roots from the motherland is what keeps us divided. But the only difference in each of us is the cultures we are accustomed to because it is part of our identity. By portraying people living on other continents connected to Africa, Canty wants us to know that until the veil of ignorance is removed from our eyes many of us will never realize that we are children of African Roots.

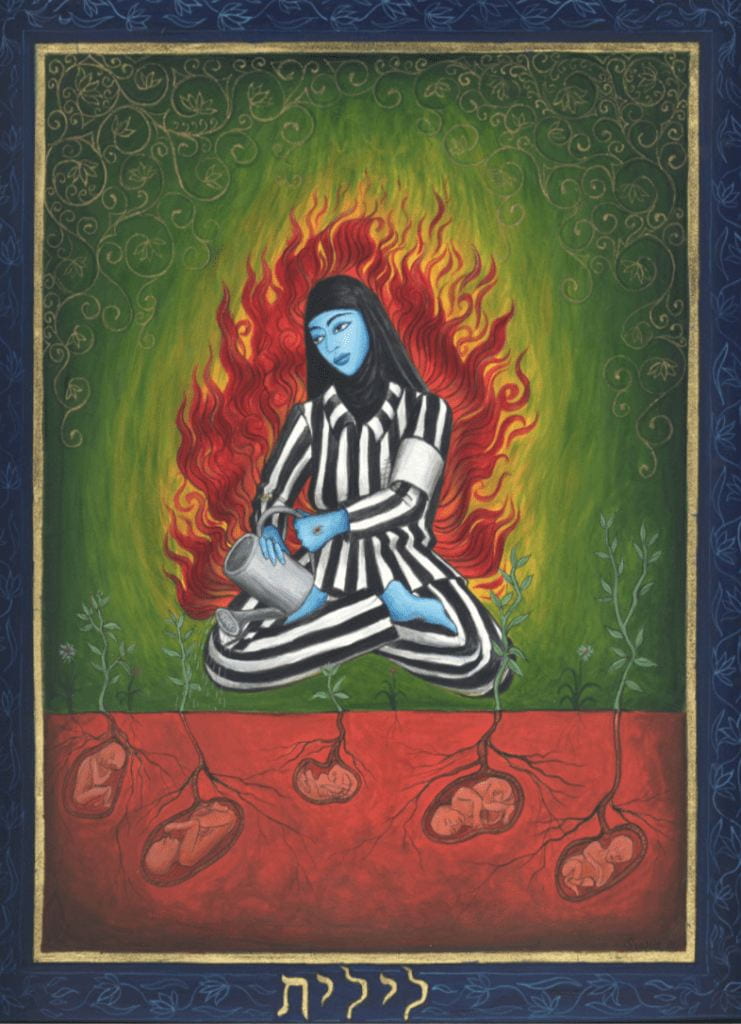

In feminist mythology and midrash, Siona Benjamin depicts Lilith as the first woman and mother. Lilith is portrayed as a Holocaust survivor as well as a Palestinian refugee in “Finding Home #68” Lilith sits in the center, cross-legged, surrounded by a raging fire. In addition, Lilith is dressed in a hijab and the uniform of a concentration camp. She has stigmata on her left hand. Stigmata are scars and wounds on the hands, wrists, and feet that are used as a universal symbol of persecution and sacrifice. Benjamin used Lilith’s image to emphasize how she is oppressed by her own people while tending to her saplings that will not grow. They aren’t rooted to the earth in life, according to Benjamin, but rather “buried from yesterday’s battles and conflicts.”

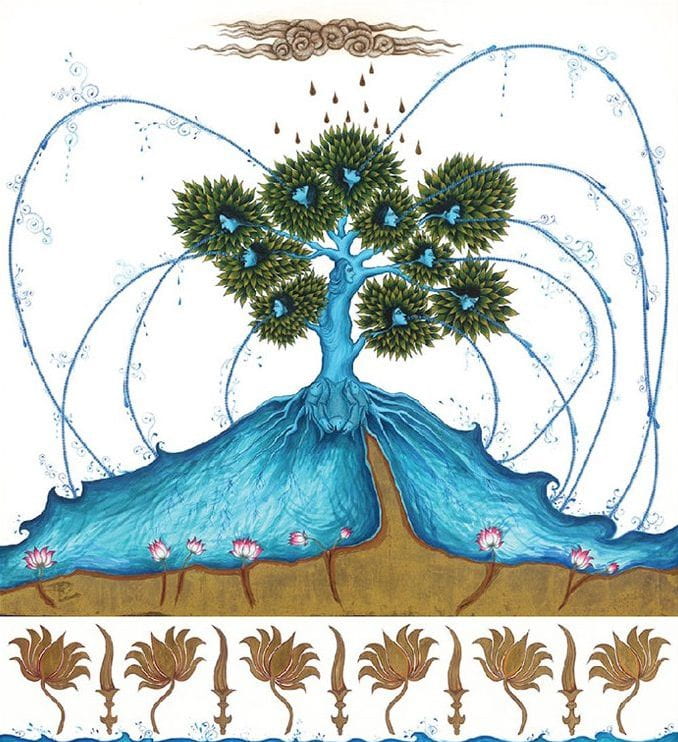

Another work of Siona Benjamin is Finding Home #86 “Chavah,” who is portrayed as the world’s first woman and her sin which led to her banishment from the tree of Eden. The tree has seven heads and is blue (six attached to the branches, and one in the roots). In Benjamin’s painting, Eve has become attached to the tree. In response, Benjamin points out that misogynistic interpretations of the Bible frequently portray Eve as “empty-headed” and a “temptress.” However, because Eve is called “the mother of all life” (“Chava” from the root “chai,” Genesis 3:20), she cannot be viewed as a destroyer. “The eating of the forbidden fruit can be looked upon as not negative or impulsive. But as a woman full of curiosity, who reaches out for the gifts of life: pleasure, beauty, and wisdom.”

Siona Benjamin depicts the idea of finding home in which “her feeling of being unable to establish deep roots anywhere unnerves her yet also pulls her toward a seductive spiritual borderland.” Both of Benjamin’s pieces remind me of our ancestors from which we are rooted. Holding on to our roots is a very compelling way of thinking about our connection to our ancestors and homelands. We are a steamed lineage with roots that provide us with stability. This indicates that everyone is globally rooted as a result of our individual identities and nostalgia for the motherland. The artwork of fetuses being rooted to their mother (Finding Home #68) can be identified as the rebirth of our ancestors because internally we are deeply rooted in the everlasting presence of our ancestors in which we exhibit and receive district traits from them.

I can also connect these images to the Jewish and African Diasporas. I think the fact that both the African and Jewish diasporas were victim diasporas, as opposed to voluntary, makes the culture that surrounds each group more similar. They have all experienced the trauma that came with their diaspora (whether it was ethnic cleansing or slavery) that gave them something “in common. They are trauma bonded and so are their children and grandchildren due to generational trauma. After these groups dispersed to different places, their cultures changed and altered based on where they ended up, typically due to the assimilation that took place after they got there. Even if their cultures became fundamentally different, they all still had one traumatic event in common which brings them together (their roots and history) no matter how much distance is between them.

The importance of concepts like “homeland” and staying connected to one’s roots are seen often in immigrant communities and in the African diaspora. Philosopher Kwame Appiah explains how African slaves preserved their dignity by remaining engulfed in African religious traditions. While these individuals pretended to accept Christianity and the colonizers’ syncretisms, this allowed for the preservation and growth of African culture and resistance to Western colonialism. Staying connected to culture is important to the African diaspora because members of the African diaspora were uprooted from their homeland and never really got the chance to accept their forced movement. Therefore this enables them to want to be reconnected to the idea of returning to their homeland and having a deeper understanding of their cultures.

Scholar Albert Raboteau states “they are in the breast of the woman,/they are in the child who is wailing.” This quote can be connected to all 3 of my images because to be in someone’s breast is similar to being in someone’s heart, but it could also mean that our ancestors reincarnate in the new generations. Raboteau explains how newborns are identified as the reincarnation of ancestors in some African religions. This detail further supports the idea of the everlasting presence of being rooted by our ancestors. Africans have a deeply rooted ancestral past that is honored in many ways and more closely felt (or so believed) when on the true land. Being forced onto new soil has made it harder for Africans to preserve their beliefs and customs.

Sources

Wecker, Menachem. “Siona Benjamin’s Blue Angels.” The Jewish Express, December 23, 2009. https://www.jewishpress.com/sections/siona-benjamins-blue.

Baskind, Samantha. “Siona Benjamin Paints Lilith of the Present.” Lilith Magazine, March 11, 2021. https://lilith.org/2021/03/siona-benjamin-paints-lilith-of-the-present/.

Canty, Malik S. “African Roots.” LetterPile. LetterPile, April 25, 2019. https://letterpile.com/poetry/African-Roots.

Benjamin, Siona. “Finding Home Series: Siona Gold Leaf Art: The Art of Siona Benjamin.” The Art of Siona Benjamin., December 17, 2020. https://artsiona.com/paintings/finding-home-2/.

Soltes, Ori Z. “Finding Home: The Worlds of Siona Benjamin.” Finding Home: The Worlds of Siona Benjamin. Accessed April 10, 2022. https://artsiona.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Margsep15-044-55-Profile-copy.pdf.

“Siona Benjamin Paints the World with a Multi-Cultural Lens.” Alberta Jewish News, November 24, 2021. https://albertajewishnews.com/siona-benjamin-paints-the-world-with-a-multi-cultural-lens/.