Duerell Bard

Transcript

Artist Siona Benjamin was born and raised in Mumbai, India within the Bene Israel community, who has long made their home in western India. There are three historic Jewish communities in India: the Cochin Jews of the Malabar Coast in the southwest, the Bene Israel of western India, and the Baghdadi Jews from the middle countries of the Ottoman Empire, who settled primarily in Bombay and Calcutta. According to the stories of Bene Israel community, they have been settled in India for over 2,000 years, bringing only the Hebrew Bible with them after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. (Boykin 31)

Scholar Joan Roland writes: “Bene Israel communal traditions maintain that they are the descendants of the ten lost tribes of Israel, their ancestors having left Palestine in the second century B.C. to escape the persecution of Antiochus. A shipwreck allegedly deposited seven men and seven women near Nawgaon on the Kokan coast, south of Bombay. Spreading out into the nearby villages, the Bene Israel were cut off from the mainstream of Jewish life until the eighteenth century, but nevertheless managed to celebrate some essential holidays, practice circumcision, follow dietary laws, and observe the Sabbath” (Roland 77).

In 1947, at the time of the Partition of India into two nations—India and Pakistan—the Jewish population of India was estimated to be approximately 26,000 people. Beginning in 1948, after the Holocaust and the founding of the state of Israel, many of the over 12,000 Bene Israel people migrated to Israel, leaving approximately only 4,000 Bene Israel people in India today. The Indian Jewish community of Israel is now somewhere between 85,000-100,000 people. According to Professor Joseph Hodes, when the Bene Israel community migrated from India to Israel, many Indian Jews faced discrimination and racism, much like other Jews of color from the Mizrahi (Jews from Arab countries) and Sephardic communities. (Boykin 31-32)

In 2011, Siona Benjamin was awarded a Fulbright to document the Bene Israel community in India and, in 2017, she was awarded a Fulbright to document the Indian Jewish community in Israel. This exhibition includes works from her Fulbright India Series, which seeks to document the personal and communal history, stories, and traditions of members of the Bene Israel. In each piece, she has created photo collages in which members of the Bene Israel community are pictured with symbols that signify things that are meaningful to them, and which are representative of their point of view. In Fulbright Series #5 Eddnah Samuel (Akshikar) photographs of Eddnah Samuel holding a bow and arrow are replicated in a circle with a Star of David in the middle. This piece can be interpreted in multiple ways; we might read Eddnah Samuel to be protecting her son from the challenges before him, or to symbolize her efforts to preserve Jewish tradition for the next generation. Surrounding the Star of David, with bow in hand, she seems to be protecting the community and values that are dear to her. Additionally, the collage’s background is ocean blue, the color that Benjamin uses in most of her works. She normally describes the blue as signifying the experience of “belonging nowhere and everywhere.” This blue background is contrasted with a deep red Star of David, which seems to emphasize the meaning and value of the symbol.

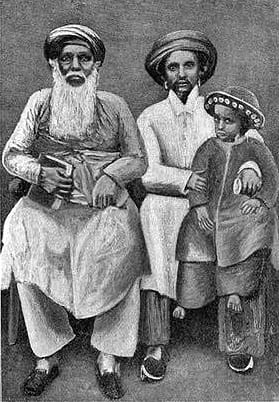

Scholars generally agree that the Bene Israel faced very little persecution in India in comparison to other Jewish communities throughout the world who have suffered various types of antisemitism for centuries. Although, Indian Jews did not face persecution, they struggled to maintain their cultural and religious traditions as a small minority in India and, at times, there was strife between the different Jewish communities. For example, Baghdadi Jews sometimes voiced racist and classist sentiments, criticizing the Bene Israel community because they were not as “fair-skinned” or as “cultured” as Baghdadi Jews. Joan Roland writes: “This cleavage had appeared by 1870 and continued to manifest itself throughout the early twentieth century, as the Baghdadis established their schools, synagogues, and trusts and attempted to exclude Bene Israel from fully participating in them” (Roland 79).

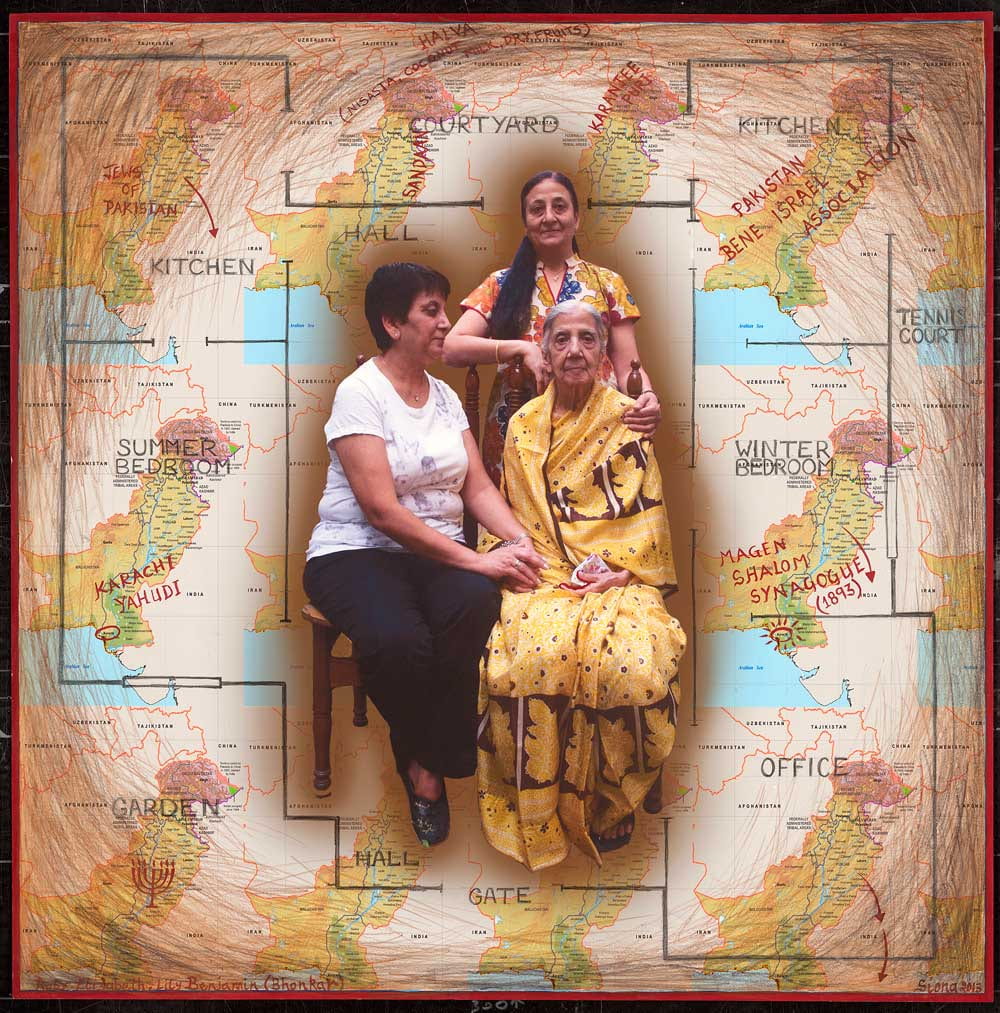

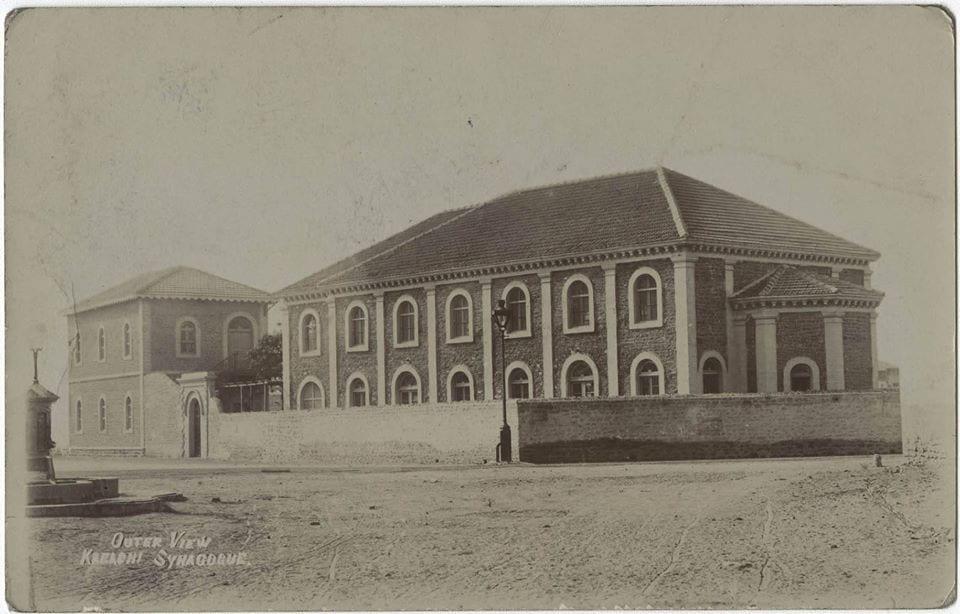

In both Fulbright Series #34 (Ruby, Elizabeth, Lily Benjamin Bhonkar) and Fulbright Series #12 (Lt. General Jack Jacob [and Pal Singh Gill, his lifelong assistant), Benjamin placed maps behind the photographs in the foreground. In Fulbright #34, drawn on top of the map, which she has labeled with things such as “Jews of Pakistan” and “Karachi Yahudhi”, she has placed a sketch that resembles a blueprint of a house with labeled rooms. Right next to the room marked “winter bedroom”, Benjamin has written “Magen Shalom Synagogue” founded in 1893— the last synagogue for a tiny Jewish community living in Karachi, which was targeted and vandalized numerous times following the Partition of India in 1947 and founding of the state of Israel in 1948. The synagogue, which also was called the “Bani Israel Masjid” was demolished in 1988 and replaced by a commercial plaza (Khurram Shopping Mall). Another subsection of the house is labeled “kitchen”, next to by the words “Pakistan Bene Israel Association.” (Weil 701-702) The Pakistani Jewish community has only about 200 members left and is on the brink of disappearing. From this, Benjamin emphasizes the origin of the Bene Israel people and the traditions that have been lost as a result of the migration of Jews out of Pakistan, which followed the waves of emigration of Jews out of Arab lands from 1948 through the 1970s.

Benjamin’s Fulbright series #8 Hannah (Munmun) Emanuel Samuel (Pezarkar) places Hannah in the center with eight extended arms. Six of the arms are holding out plates with food and the other two are mixing a pot of food. Benjamin seems to be alluding to the Hindu goddess Durga in her representation of Munmun with multiple arms. The Goddess Durga is often said to symbolize female power, determination, and hope, something the Bene Israel women seem to embody. (Amazzone 4)Benjamin could also be expressing Munmun with multiple arms extended out as a way of showing the gift of sharing Bene Israel traditions. One thing that is interesting about this piece is that Benjamin used turmeric spices throughout the piece, a spice that Munmun most certainly used in her cooking, maybe even in that pot she is stirring. The use of these spices gives the painting a more gives it a vivid orange background.

In contrast to the voluntary migration of many Bene Israel Jews to Israel over the past 70 years, Siona Benjamin’s Exodus: I See Myself in You depicts for us the struggles of immigrants. Benjamin harkens back to the Hebrew Bible, referencing the journey of the Israelites from slavery to freedom, as well as the oppression, persecution, violence, and suffering that precipitated many migrations throughout Jewish history. Although referencing the biblical and Jewish narratives, this piece—inspired by migration crises such as the forced exodus of Syrian refugees—seeks to tell a more universal human story, about the struggles of migrants everywhere past and present. In the first panel, Benjamin paints a struggling man holding a ram, which is a biblical reference to Abraham in the Bible. In the story of Abraham, he was asked to leave his home in Mesopotamia because God told him to search for a new land, which even though “Promised” was not free from challenges or strife. Like the biblical Abraham, it seems, the Bene Israel faced many challenges in their migration to the “Promised Land.”

In her research on the Bene Israel community in Israel, Scholar Schifra Strizower documents an elder in the community saying: “Gradually, we found that our children could not get education nor the adults among us any jobs to maintain ourselves and our families. We had to sell what all we had brought, including clothes and neither the people nor Government of Israel care for us” (Strizower 125). The Bene Israel clearly had to make tremendous sacrifices in their migration to “paradise.” At the bottom of the first panel, a woman holds a child and is trying to comfort it. Benjamin seems to remind us of the pain and anguish that can be involved in any journey, even if in search of a new land and home where generations could come to thrive. In the second panel, a sitting woman seems to be in pain or grief from the migration; perhaps she is asking God for acceptance. As stated by Strizower, “Many Bene Israel hoped that migration to Israel—which in the absence of repressive measures against Jews in India might be interpreted as an expression of Jewish solidarity and love of the Holy Land—would result in complete acceptance by other Jews” (Strizower 123). That, however, was not the case, the Bene Israel like other Jews from Mizrahi and Sephardi communities were subject to discrimination from some Ashkenazi communities. So too migrants, viewed as ‘Others’ often face new forms of discrimination and challenges in their new home.

In the third panel, a woman walks with her belongings and is surrounded by angels who seem to be in distress, doing everything they can to protect the women from harm. The fourth panel is represented by an angel. Angelic figures are commonly referenced in Benjamin’s work. Although in the central panel, this angel isn’t supposed to be a subject of veneration. Instead she seems to want viewers to place themselves in the skin of the immigrants; the angels seem to be giving the immigrants strength, bolstering their hope of finding a home. (Sippy 23). In the fifth panel, a woman is carrying a child but is accompanied by five female figures who are crying. These women may be crying because they are being punished and there appears to be nothing that they can do about it as they fear for the safety of the child. In the sixth panel, a woman is laying on the ground sleeping and a devilish-looking figure stands over her. Perhaps the demonic figure represents the trials and tribulations the child or generation down the road may face without the protection of Jewish traditions, one’s traditions lost as a result of the Bene Israel community’s migration to Israel. Also, in this panel, a man walks away from the woman with all his stuff in hand. In the last panel, Benjamin depicts a woman holding on to a young child as a man walks away. The man walking away could represent some of the old customs followed by the Bene Israel people that are being left behind from their migration from India to Israel.

In conclusion, the Bene Israel people faced many forms of discrimination during diaspora. Siona Benjamin explores for us the theme of personal importance that the Bene Israel people assign to their community and their roles in the community. As Benjamin explores this theme of community she reminds us of the sometimes good, and sometimes bad that comes from living in a minority group, in the larger social world.

Sources

Amazzone, Laura, Goddess Durga and Sacred Female Power, 2010: Hamilton Books

Mahim Maher, “The Jews Built Karachi, but we built shopping plazas on their synagogue,” The Express Tribune, November 3, 2013. https://tribune.com.pk/story/626468/secret-histories-the-jews-built-karachi-but-we-built-shopping-plazas-on-their-synagogue

Joseph Hodes. From India to Israel : Identity, Immigration, and the Struggle for Religious Equality. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2014. EBSCOhost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=784496&site=ehost-live.

Strizower, Schifra. “The ‘Bene Israel’ in Israel.” Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, Taylor & Francis, Ltd., 1966, pp. 123–43,

Roland, Joan G. “The Jews of India: Communal Survival or the End of a Sojourn?” Jewish Social Studies 42, no. 1 (1980): 75–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4467074.

Robbins, Kenneth X. and Tokayer, Marvin, ed. Jews and the Indian National Art Project. New Delhi: Niyogi Press, 2015.

Boykin, James H. Black Jews Ethiopia, India, United States. Library of Congress Card Catalogue, 1982.

Weil, Shalva. “What Happened to Pakistan’s Jews?“, 2011. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Shalva-Weil/publication/317957572_What_Happened_to_Pakistan%27s_Jews/links/5954c06fa6fdcc16978c9aa2/What-Happened-to-Pakistans-Jews.pdf.