Aliana Conway

FINDING HOME #68 BY SIONA BENJAMIN

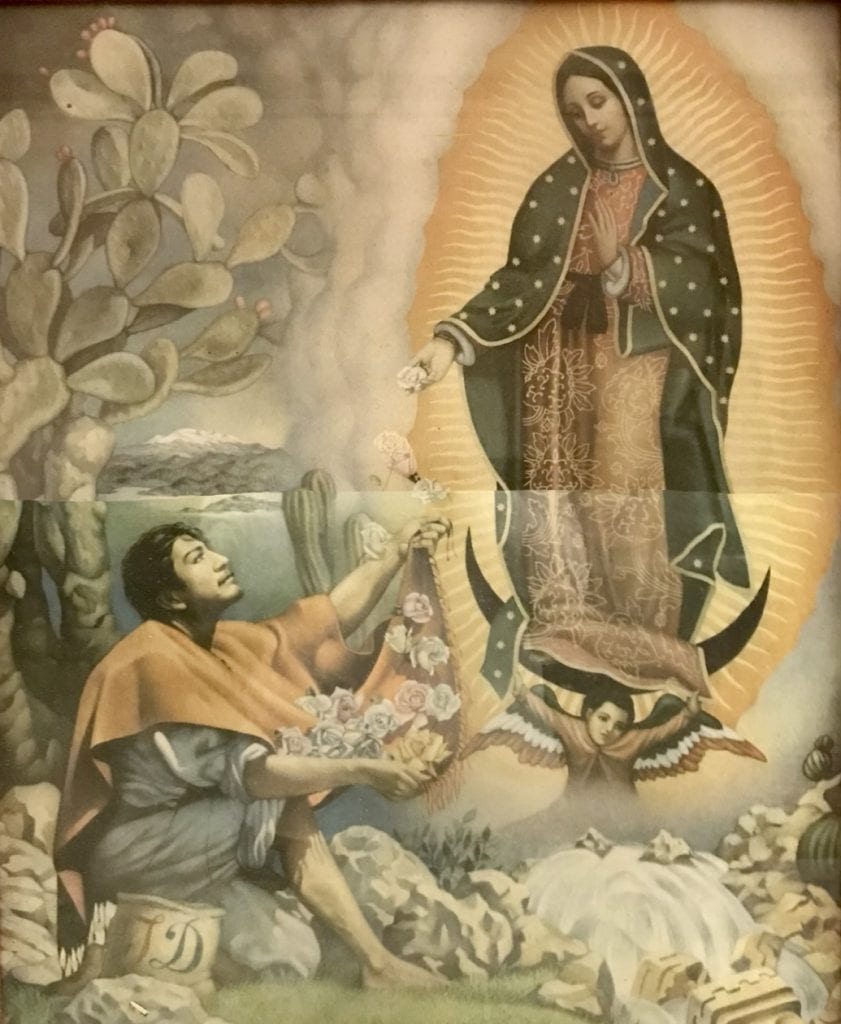

NUESTRA SEÑORA DE GUADALUPE Y JUAN DIEGO

Transcript

Throughout my childhood, my mother, a chicana woman from South Texas, would tell me stories of her youth while driving me to school every morning. She told me about going to Mexico, visiting family and farms, detailing the unique experiences she holds as a member of a Mexican family.

I remember one story in particular about my bisabuela, or great grandmother, Anita de León Saavedra. One time, after she and my mother rode the train to Mexico to visit family, chat with friends, and pick up special groceries like Mexican vainilla that you can’t find in the United States, they also visited the Basílica de Santa María de Guadalupe, or the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe. As they arrived within view of the Basilica, my mother and bisabuela knelt and began crawling up the stairs of the house of worship. This may seem silly or strange, but to my bisabuela, it was a necessary display of love, humility, and worship.

Anita and her family revered Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, or Our Lady of Guadalupe. Keep in mind that there are many names for Mary, mother of Jesus, in the Catholic faith. Each reflects a different form that she takes: Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, or Our Lady of Guadalupe, is the apparition of Mary to Juan Diego, an 16th century indigenous man from Mexico; La Virgen Morena, or the Brown Virgin, refers to the Mexican ethnicity and dark skin color of the apparitional Mary. Mary holds many titles, but ultimately, all refer to the beloved Mother of God.

In addition to being the Mother of God, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe is seen as a mother to Latinos and specifically mexicanos including my bisabuela Anita. Just as mothers are responsible for protecting their children, la Virgin Morena is credited with keeping Latino and, specifically, mexicano migrants safe in the diaspora.

The significance of the Virgin Mary for Latinos migrating to the United States is reflected in the rosaries and images of the Virgen they often carry with them across the border. Tom Kiefer, an artist and previous part-time janitor for a migrant detention center in Arizona, collected the confiscated property of Latino migrants instead of throwing it away. He photographed these items and published the photos as part of his project, El Sueño Americano (“The American Dream”). Two of the most shocking and insightful images featured figurines of Our Lady of Guadalupe and rosaries confiscated by border patrol agents because they were deemed “non-essential” or “possibly lethal.” Kiefer’s discovery exemplifies the significance of Virgen to Latinos and the significant number of migrants, including my bisabuela‘s family, who pray to her for safety and comfort.

Latinos continue to revere la Virgen Morena in the United States as a way to stay connected to their identity and combat the stress of living as a minority. Sacred Minnesota is a documentary short about Mexican immigrants’ devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe to combat the loneliness they feel after immigrating to the US. **Gloria, an interviewee in the documentary, joined a Catholic Church and created her own altar with spiritual images of the Virgen to remember her home and her country. **Gloria’s actions are common solutions among Mexican immigrants.

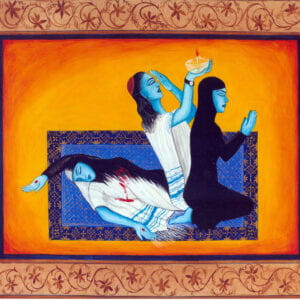

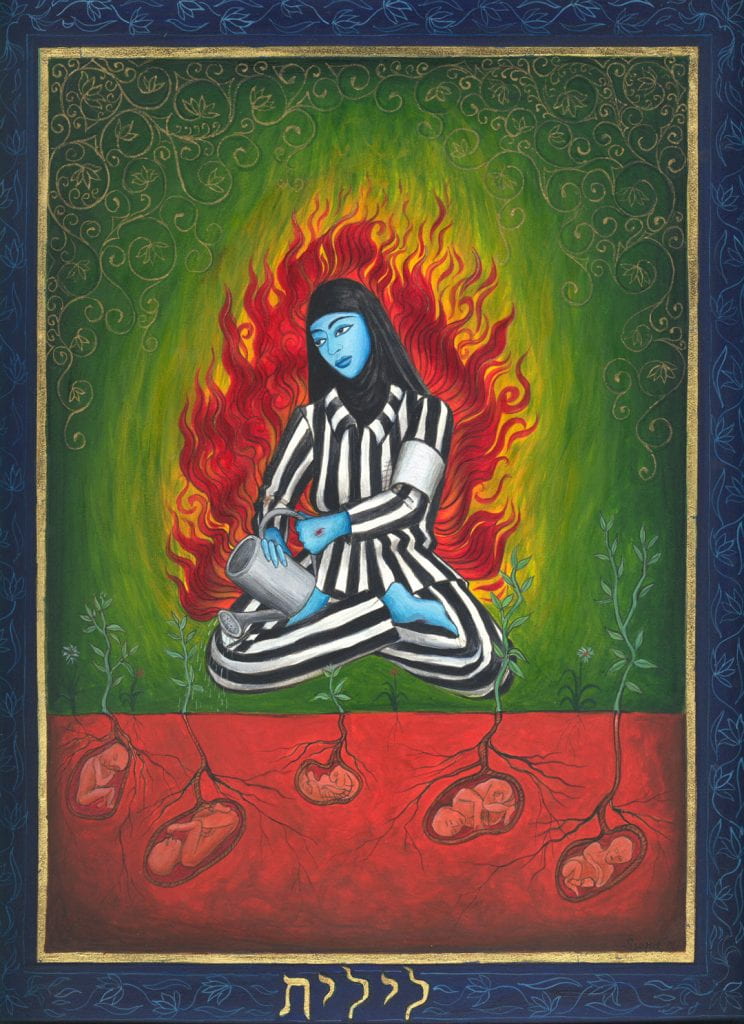

The image of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe y Juan Diego is an image passed down in my family so that future generations can remember our culture and religious identities. Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe y Juan Diego relates to Finding Home #68 of Siona Benjamin’s much larger Finding Home series, and there are many similarities between the depictions of Lilith, who is imagined as the first woman and mother in midrash and feminist mythology, and the Virgen. In Benjamin’s piece, Lilith, wears a hijab; likewise, the Virgen wears a veil. In addition, Lilith has multiple stigmata in her hands and feet. Stigmata, or wounds and scars in the hands, wrists, and feet, is a universal symbol of persecution and sacrifice. In Catholic catechism, stigmata relate to the Passion and Crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Saints are often depicted with stigmata to represent their empathy and spiritual presence at the Passion of Jesus. Benjamin’s choice to include stigmata on Lilith’s hands and feet relates Lilith to the Virgin Mary, who was physically present at Jesus’s death, and adds a critical dimension of suffering and persecution to Lilith’s character.

In terms of the whole images, the two are visually similar. Just as Lilith looks lovingly upon the fetuses she waters, Mary looks down upon Juan Diego, the legendary recipient of her image in his tilma, or cloak. These loving looks portray motherhood in addition to the cultural identifiers in each work. Mary wears the patriotic colors of red, white, and green, and the Mexican flag is imprinted on the wings of the angel. Nopales, or the prickly pear cactus native to Mexico, grow in the background. However, these prideful and patriotic symbols contrast against symbols in Benjamin’s piece which reflect suffering. In addition to featuring the stigmata, Lilith wears a hijab and concentration camp uniform. These two articles of clothing simultaneously identify Lilith as a Palestinian refugee and as a concentration camp victim – quite the anomaly considering how Israelis and Palestinians are often seen at odds.

Benjamin’s choice to present Lilith, the first mother, as both of these contradicting characters represents the interconnectedness and shared experiences of mothers who are uprooted from their homes and forced to rewrite their identity in a strange, new world. They both face the questions: how will I pass down my culture to my children? How will my children know their identity? What will the future look like for this new generation? These questions generate angst and existential struggles for women who have no choice but to continue caring for their children. Finding Home #68 displays this struggle shared among refugees, migrants, and persecuted peoples across the globe. Just like these people, Lilith must continue to water and care for the next generation. Siona Benjamin’s own interpretation of this work implies that, despite the care of the mother, the children will never grow. However, I see Lilith as a model of strength whose loving care helps the new generations create roots in new land.

Just like Lilith, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe helps Latino migrants place roots in the United States. When people are faced with the unknown, they often turn back to tradition and religious roots. Latina mothers pass down their stories and the importance of the Virgen in a collective memory to their children. My own mother told me stories of her chicana childhood not only to entertain me on the way to school, but also to fill me with cultural knowledge that I couldn’t get from class. Passing down the Virgin teaches each new generation about their culture and their identity; who they are, what they believe in, and what they stand for. Our Lady of Guadalupe ties each mexicano and chicano back to the homeland, and it ties each Latino Catholic back to basic tradition. To put it simply, Our Lady of Guadalupe is an answer to the questions posed by mothers in diaspora.

Sources

O’Loughlin, Michael J. “Why a Janitor Saved the Rosaries Confiscated at the Mexican Border.” America The Jesuit Review, 26 June 2018, https://www.americamagazine.org/arts-culture/2018/06/26/why-janitor-saved-rosaries-confiscated-mexican-border. Accessed 14 March 2022.

“Our Lady of Guadalupe Unifies MN Latinos.” Sacred Minnesota, season 2, episode 4, Twin Cities PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 15 June 2021, https://www.pbs.org/video/our-lady-of-guadalupe-unifies-mn-latinos-38791/. Accessed 14 March 2022.

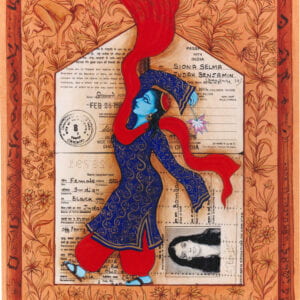

SIMILAR WORKS BY SIONA BENJAMIN

SOURCES FOR FURTHER LEARNING