Shana Sippy • Assistant Professor of Religion • Centre College

I first encountered the work of Siona Benjamin when I was in my late 20s. For perhaps the first time in my life, I saw many of the complex layers and dimensions of my own identity expressed in artistic form.

I first encountered the work of Siona Benjamin when I was in my late 20s. For perhaps the first time in my life, I saw many of the complex layers and dimensions of my own identity expressed in artistic form.

Siona Benjamin was raised in Mumbai as a member of the Bene Israel community, one of India’s three historic Jewish communities—the other two being the Malabari Jews of Cochin and the Baghdadi Jews. The urban metropolis of Mumbai is home to many religious communities—Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Parsis, and Buddhists—whose rich traditions inform her work. Benjamin migrated to the United States in 1986 to pursue her education, eventually settling in New Jersey.

As the daughter of an American Jewish woman from New Jersey and an Indian Hindu-Sindhi father from Mumbai, the affinities between my own life and Siona’s were significant. The symbols, languages, artistic styles, narrative allusions, and historical references in her paintings were familiar to me. And, although my own background is actually quite different from Benjamin’s, her art has always resonated with me in profound and personal ways. While her work speaks uniquely to the experiences of Indians, Jews, feminists, and American immigrants, Benjamin’s pieces transcend the particularity of those identifications. She wrestles with broad human questions about home and belonging, migration and memory, oppression and violence, loss and recovery, hope and transformation. Drawing on Indian, Jewish, Persian, Hindu, Islamic, and Christian, as well as American and popular cultural artistic forms, Benjamin’s eclectic style, like she, refuses simple categorization.

In naming this exhibition Beyond Borders: The Art of Siona Benjamin, we seek to explore—in particular—the ways in which Benjamin’s work asks viewers to consider what it means to stand on the margin between worlds, to both confront and cross established boundaries. Furthermore, Benjamin’s work inspires us to think about how the very same things that may nurture us and make us feel at home, can be the cause of alienation and marginalization for others.

Strikingly, Benjamin’s female subjects are almost always blue. Stylistically, she borrows from a Hindu artistic tradition in which the gods Krishna, Rama, Shiva, and the goddess Kali are often rendered this color. In painting the deities blue, this Hindu convention references various sacred narratives and interpretive traditions, making these characters easily identifiable to viewers, signifying their other-worldliness. Choosing to draw on this tradition in her imagining of Jewish female figures—whether in self-portraits, depictions of biblical and midrashic women, angels, or other human beings—Benjamin has sought to illustrate what it means to embody difference, to be both of the world and outside of it. She intentionally seeks to draw attention to the ways that race, culture, religion, language, ethnicity, caste, or class can mark people as Others, rendering them perpetual foreigners even in their own homes.

Many of her works, especially those in the Finding Home, Exodus, and Liberty Series, are commentaries about migration and the human desire for belonging and refuge, as well as critiques about the dangers of nationalism, ethnocentrism, racism, and nativism. Benjamin’s paintings are filled with female figures dressed and adorned in ways layered with cultural significance. The vast majority of her subjects wear traditional Indian attire; however, the fabric of the saris, for example, often doubles as a tallit (a traditional Jewish prayer shawl with knotted fringes and blue and white lines). Her figures often don accessories or clothing referencing the American or Indian flags (Fereshtini #9, Finding Home #33, My America). She also combines popular cultural motifs (Mickey Mouse [Finding Home #29], Power Puff girls [Finding Home #49], Bugs Bunny [My America]) with Jewish symbols (tefillin/ phylacteries, a menorah). Through these sartorial allusions to nationalism, religion, and popular culture, Benjamin demonstrates the contingencies of our identities. Sometimes we may be oppressed by these associations, other times they are liberatory. Her self-portrait of a multi-armed woman holding Uncle Sam’s hat aloft (Finding Home #33) suggests that there may be aspects of ourselves that we cling to, assume temporarily, or at times choose to discard.

Complex and layered identities are sources of both strength and conflict. Benjamin imagines home through an array of cultural symbols and the use of multiple languages (Hindi, Marathi, Urdu, Hebrew, English). Some references in her work may not be familiar or legible to specific audiences; her artistic choice mirrors how immigrants must navigate and decipher myriad cultures, ways of knowing and being. Finding a home, Benjamin suggests, is not about leaving one’s religious and cultural worlds behind but creating a new vision for oneself and of oneself. She envisions home on the borderland between worlds. From that margin, it is possible to see things that are otherwise imperceptible to others, to understand and empathize with experiences that might seem foreign to those at the center.

The late Black feminist poet, scholar, and social activist, bell hooks, wrote of finding home in this marginal place. The “meaning of ‘home,’” she asserts, “changes as a result of experience.”

At times home is nowhere. At times one only knows extreme estrangement and alienation. Then home is no longer just one place…. Home is that place which enables and promotes varied and everchanging perspectives, a place where one discovers new ways of seeing reality, frontiers of difference. One confronts and accepts dispersal, fragmentation as part of the construction of a new world order that reveals more fully where we are, who we can become, an order that does not demand forgetting.

Living “on the edge,” hooks suggests, created a space that enabled Black people in her community to develop “a particular way of seeing reality,” looking “both from the outside in and from the inside out.” hooks does not wish to romanticize the experience of marginality that is, for so many, a place of despair and deprivation “imposed by oppressive structures.” However, she believes that it can be a “location of radical openness” and a “site of resistance” to forms of domination precisely because from there one cannot forget those who have been cast aside. Able to access different worlds, the margin is a space that invites creative “conceptualizing [of] alternative ways of being.” Siona Benjamin has chosen the margin, inhabiting and expressing the border-experience in her work and creatively reconceptualizing ways of being, remembering, and envisioning home and our place within the world.

This exhibition showcases seven pieces from Benjamin’s Finding Home Series, the vast majority of which are modern, visual midrashim (creative interpretations) of figures in the Hebrew Bible or rabbinic literature. In addition to her many re-imaginings of the midrashic figure Lilith (the first woman, created as an equal to Adam before Eve), this exhibition includes a piece in which she recasts a rabbinic legend about four rabbis who enter paradise imagining how it might have been if it had been the four matriarchs of Jewish tradition instead (Four Mothers Who Entered Pardes).

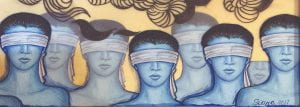

Benjamin is particularly partial to the Book of Esther—the only book of the Hebrew Bible to take place entirely in the diaspora, and which speaks powerfully to the experiences of minorities and the challenge of assimilation. In multiple pieces, one of which is included in this show, Benjamin depicts blindfolded women, representing embodiments of Esther; in Improvisation #25, Esther’s name is written upside down in Hebrew above billowing blue clouds. In this story, retold each year on the Jewish holiday of Purim, Esther hides her identity as a Jew in order to win the favor of the king and become his bride. When the king’s advisor plots to annihilate the Jews, Esther reveals her true identity, an act that turns the story upside down, ultimately saving the Jewish people. Refusing to hide any longer, not only is Esther accepted for who she is, but she refuses to stay blind to the suffering of others. Esther is one of only two books in the Hebrew Bible where God is never mentioned. According to rabbinic tradition, one explanation for God’s absence is that God has hidden, a concept called Hester Panim (literally, hiding the face). The divine presence, some believe, is revealed when Esther reveals herself. Theologically, some interpreters have argued that Esther’s story is a reminder that human beings cannot wait to be saved by God; it is through taking the responsibility for justice into their own hands that God is manifest. Benjamin’s work seems to echo this sentiment. It is not God who intercedes to protect and care for the mothers, migrants, and refugees that we see suffering in her works, but it is feminine fereshteh (angels in Urdu), women like Lilith, the biblical matriarchs, members of the Bene Israel community, and Benjamin herself who symbolize hope, strength and transformation.

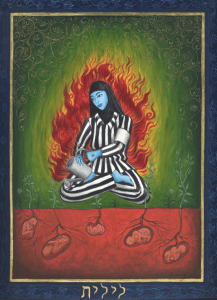

In Finding Home #68 (Fereshteh), Benjamin imagines Lilith as both a Jewish woman in the Holocaust—a concentration camp prisoner in a painfully recognizable striped uniform—and a Palestinian Muslim woman refugee. Her painting challenges viewers to see the anguish of both women; she illustrates that to acknowledge the suffering and violence experienced by one of them does not necessitate denying or turning away from the pain of the other. In painting Lilith—the primordial woman—as both women, Benjamin helps us to recognize their common humanity. On her left hand, this Lilith is marked with a stigmata—Christian symbol of martyrs and ones chosen to identify with the pain of sufferers. Painted with a watering can in hand, we come to recognize Lilith’s desires (and those of all the women and mothers that she embodies) to nurture the earth and secure the future for the next generation. In Benjamin’s words, this Lilith, “has sown many saplings and seen them grow,…tend[ing] to them carefully, building a fortress of hope.” Tragically, though, these “saplings will not grow!…They are just buried saplings from yesterday’s wars and tomorrow’s plunderings.” With an armband, left intentionally blank, to signify “the oppressed and the oppressors of the future,” Benjamin’s piece challenges us not only to see others in ourselves and ourselves in others, but to consider what might be done to transform this picture going forward.

In Finding Home #68 (Fereshteh), Benjamin imagines Lilith as both a Jewish woman in the Holocaust—a concentration camp prisoner in a painfully recognizable striped uniform—and a Palestinian Muslim woman refugee. Her painting challenges viewers to see the anguish of both women; she illustrates that to acknowledge the suffering and violence experienced by one of them does not necessitate denying or turning away from the pain of the other. In painting Lilith—the primordial woman—as both women, Benjamin helps us to recognize their common humanity. On her left hand, this Lilith is marked with a stigmata—Christian symbol of martyrs and ones chosen to identify with the pain of sufferers. Painted with a watering can in hand, we come to recognize Lilith’s desires (and those of all the women and mothers that she embodies) to nurture the earth and secure the future for the next generation. In Benjamin’s words, this Lilith, “has sown many saplings and seen them grow,…tend[ing] to them carefully, building a fortress of hope.” Tragically, though, these “saplings will not grow!…They are just buried saplings from yesterday’s wars and tomorrow’s plunderings.” With an armband, left intentionally blank, to signify “the oppressed and the oppressors of the future,” Benjamin’s piece challenges us not only to see others in ourselves and ourselves in others, but to consider what might be done to transform this picture going forward.

In Finding Home #29 Benjamin imagines a mythical creature, part woman, part lion, part machine. Escaping destruction, Benjamin imagines the creature taking “one last glance” at her burning home, fleeing in fear of “the pollution and atomic explosions.’ Unplugged, she takes she takes refuge in Jewish tradition, saying the Shema, the central Jewish affirmation and prayer in hopes for “a good voyage home.” In this early piece, Benjamin has not yet become blue, but she already imagines herself to be a kind of mythical, shape-shifting creature—part woman, part lion—who needs to change form in order to adapt to new circumstances and contexts. Also displaying her wit and humor, Benjamin shows how this being needs to accustom herself to new cultural symbols, like the Mickey Mouse slippers on her paws. The electrical cord is reflective of the various ways we might read this piece—is she unplugged (with a cord that will require a new adapter to be plugged into her new home), is she leaving the culture and comforts that gave her energy in order to undertake this journey, will she be electrocuted since electricity and water don’t mix?

The Exodus Series: I See Myself in You points to the ways in which history continues to repeat itself, drawing connections between the biblical Exodus from Egypt and various migrations throughout both Jewish and world history. These works simultaneously capture the human quest for paradise and home and poignantly illustrate the struggle and pain of refugees whose lives have been ravaged by war, genocide, religious and ethnic strife, environmental and economic devastation, nationalistic fervor and xenophobia. Some pieces in the series feature angels and birds, symbolizing hope and the promise of flight to a new world (Exodus #1 and #11. In others we encounter those who are in denial, unable or unwilling to remove their blinders (Exodus #6), to see the refugees fleeing, struggling, and praying (Exodus #7 and Exodus: I See Myself in You).

Exodus: I See Myself in You is a seven-panel piece, which illustrates the hardship and pain of migration. Alongside weeping mothers, people carrying their children and their worldly possessions, and a man holding a ram—perhaps a reference perhaps a reference to the ram provided to Abraham as the substitution that saved him from sacrificing his son Isaac—there are winged-angels, helping guide the refugees to safety, while menacing figures create obstacles along the way. In the first panel, a woman caresses her child in what looks like the mouth of a whale, an allusion to the prophet Jonah who attempted to run away from his God-given mission to beseech the residents of Nineveh to turn away from their evil ways and repent. Unlike Jonah, whose attempt to flee is willful, the refugees in Benjamin’s piece embark upon their dangerous journeys because they have no choice.

Like a number of her other works, here Benjamin draws inspiration from Christian altarpieces. Intended to cultivate a prayerful disposition, altarpieces focused worshippers on a specific religious narrative and its lesson about the divine role in one’s personal salvation. Here, Benjamin diverges from the Christian artistic convention. In this polyptych’s center panel, we find a striking female angel, one of many divine messengers who appear frequently in her work. In theological contexts, angels are traditionally envisioned as occupying liminal space, mediating between heaven and earth. In artistic renderings, angels are normally placed, quite literally, on the margins, supporting the more religiously significant figures. In Benjamin’s work, the female angel is the central figure; however, she is not intended to be worshiped. Instead, as the subtitle of the Exodus Series “I See Myself in You” suggests, Benjamin asks her audience to see themselves not only in the refugees but also in the angels, the intercessors who offer those in despair hope and strength.

Benjamin often invokes the messianic vision of Tikkun Olam (repair of the world), a kabbalistic idea that enjoins human beings to be active participants in transforming, redeeming, and repairing the world. In this way, much of her work can be seen as a plea and a form of prayer.

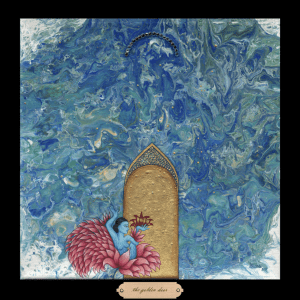

The Liberty Series is a visual meditation on Jewish writer Emma Lazarus’ 1833 poem, the “New Colossus,” which is famously on the pedestal of the “Mother of Exiles,” the Statue of Liberty. In a constellation of 14 pieces, Benjamin envisions “vulnerable bodies”—falling, “tired,” “poor,” “huddled,” “tempest tossed” and “homeless”—seeking refuge, “yearning to breathe free.” She holds out Lazarus’ words like a prayer, hoping that there will be someone to light the way to the “golden door.” Created in 2018, the work is a reflection on both past and present migrations. Her piece gestures specifically at the Jewish immigrants who came via Ellis Island, fleeing pogroms and economic hardship in Eastern Europe in the late 1800s and early 1900s, some of whom may have even encountered Lazarus’ words on Lady Liberty. Yet, Benjamin’s painting is also a searing commentary on the contemporary moment. She calls to mind refugees from Syria, risking everything to flee genocide, some of whom were washed ashore dead, and those refugees on the US-Mexico border, from Afghanistan, Myanmar, and elsewhere, who have been turned away, treated as “wretched refuse,” unwelcome, and unable to find safety. While politicians have painted refugees as foreigners to be feared, Benjamin asks us to see them as beautiful and resourceful beings, some of whom are winged-angels,  whose suffering we must strive to end and whose gifts—like lotuses that bloom from muddy waters—we have yet to recognize.

whose suffering we must strive to end and whose gifts—like lotuses that bloom from muddy waters—we have yet to recognize.

Benjamin’s work suggests that finding home is not about building a house whose walls insulate us from the world around us. The migrants whose lives she beckons us to see have made homes on sandy shores, in refugee camps, even in the mouth of a whale. As profoundly difficult as it is for so many people to secure, Benjamin reminds us that shelter, nourishment, and safety— fundamental human needs and rights—should not be confused with home. Home is at once far more elusive and much more accessible.

The 20th-century Jewish theologian, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, who fled Eastern Europe in 1940 and whose family perished in the Holocaust, understood that there was a fundamental relationship between the constant search for home and the act of prayer. He wrote:

All things have a home, the bird has a nest, the fox has a hole, the bee has a hive. A soul without prayer is a soul without a home. Weary, sobbing, the soul, after roaming through a world festered with aimlessness, falsehoods and absurdities, seeks a moment in which to gather up its scattered life, in which to divest itself of enforced pretensions and camouflage…in which to call for help without being a coward. Such a home is prayer.

Benjamin’s work asks viewers to see the world from the border, through her eyes. She offers us a glimpse into the home of her soul, and invites us to join her in realizing her prayer and working to repair the world.

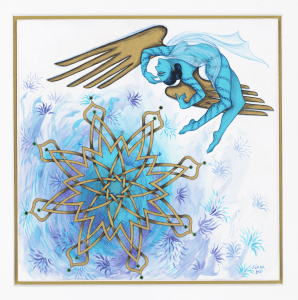

In the time of COVID • Benjamin’s Circle of Introspection Series

In this series, Benjamin draws on the Hindu and Buddhist form of the mandala, what she describes as “positive” circular mediations “in response to the negative circular COVID virus.” A tool for religious contemplation, mandalas are intended to help practitioners cultivate a practice of introspection. Since the spring of 2020, everyone has turned inward in various ways—retreating into our homes, shielding ourselves behind masks, limiting our circles of interaction. Benjamin suggests that, like her female figures who have found new ways to breathe—transcending, blowing away, and transforming the negative—with patience, self-reflection, and care, we might be able to do the same.

practitioners cultivate a practice of introspection. Since the spring of 2020, everyone has turned inward in various ways—retreating into our homes, shielding ourselves behind masks, limiting our circles of interaction. Benjamin suggests that, like her female figures who have found new ways to breathe—transcending, blowing away, and transforming the negative—with patience, self-reflection, and care, we might be able to do the same.